Filmmaking

I’m extremely proud that “Carry My Heart to the Yellow River,” the short I directed and co-wrote in China in the summer of 2018, has found such a global audience on the 2019-2020 film festival circuit. So far, this uplifting story of a high school graduate’s epic journey on behalf of her sick friend has been accepted to 45 Film Festivals among ten countries and territories, including the USA, Guam, Italy, England, India, Ireland, Bhutan, Germany, Australia, and Canada, and we’ve been semi-finalists in an additional six festivals in three more countries.

On top of all this, we’ve won an astounding ten awards, including three best short awards, two audience choice awards, and specific awards for best drama, best director short film, and best cinematography.

In the United States, we’ve had screenings from coast to coast, including but not limited to New York (Syracuse and Williamsburg), Florida (Orlando and Fort Lauderdale), California (Los Angeles, Newport, Ojai, Santa Cruz), Hawaii, Washington, and many states in-between (Mississippi, South Dakota, Iowa, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin).

Most importantly to me, audience response has been terrific, and I’ve heard from more than one viewer who’s been deeply affected by our story. After all the hard work, it’s enormously gratifying to see the emotional payoff in the faces of viewers.

Film Festivals to which we’ve been accepted:

- 39th Breckinridge Film Festival

- Great Lakes International Film Festival

- Charlotte Film Festival

- South Dakota Film Festival (Winner – Best Family Friendly Short)

- Fayetteville Film Film Festival

- Sioux City International Film Festival

- Santa Cruz Film Festival

- Syracuse International Film Festival (Winner – Short Film Fiction)

- Orlando Film Festival

- Guam International Film Festival

- 70th Montecatini International Short Film Festival

- Liverpool Film Festival

- 20th Ojai Film Festival

- East Lansing Film Festival

- Alexandria Film Festival

- 34th Fort Lauderdale Film Festival

- 39th Hawaii International Film Festival

- Goa Short Film Festival

- Williamsburg Film Festival

- Waterford Film Festival

- Druk International Film Festival (Winner – Short Film: Outstanding Achievement)

- IS Short Film Festival Pune India

- 42nd Big Muddy Film Festival

- Snowdance Independent Film Festival

- 14th Beaufort International Film Festival

- Green Bay Film Festival (Winner – Titletown Award for Best Short, Audience Choice Best Short)

- Children’s Film Festival Seattle (Winner – Best Live Action Short)

- 20th FirstGlance Los Angeles (Winner – Best Drama, Audience Choice Short Film, Best Director, Best Cinematography)

- 14th Taos Shortz (Postponed)

- Beeston Film Festival in Nottingham, UK (limited online exhibition)

- Cleveland International Film Festival (in the Filmslam program) (limited online exhibition)

- Australian Inspirational Film Festival (Postponed)

- 17th Tupelo Film Festival (Postponed)

- Tallahassee Film Festival (Cancelled)

- Tiburon International Film Festival (Postponed)

- 39th Minneapolis Saint Paul International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- Julien Dubuque International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- Newport Beach Film Festival (Postponed)

- XXI Festival Internazionale Corti da Sogni Antonio Ricci (Postponed)

- 15th European Independent Film Festival (ECU) (limited online exhibition)

- Riverside International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- 39th Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- Julien Dubuque International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- 62nd Rochester International Film Festival (limited online exhibition)

- 16th ReelHeart Film Festival (Toronto, Canada) (limited online exhibition)

Film festivals at which we’ve been shortlisted, but not accepted:

- Sapporo International Short Film Festival & Market (Programmer’s Delight Shortlist)

- Thessaloniki (Semi-finalist)

- Short to the Point Awards (Semi-finalist)

- Dublin International Film Festival (Shortlist)

- Asia South East (Highest Commendation)

- Dances With Films (Second Round Selection)

Additional Note – At this point, given the worldwide pandemic with which we’re faced, film festivals are either postponing screenings, or moving to one of several online exhibition models for limited time screenings. We fully support both decisions, and I’ll post updates for whenever online screenings are scheduled. It’s been a fantastic run so far, and we’ll see it through to the very end. I’m hoping we can find a willing streaming distributor who can provide this project with a more permanent home!

Over the years I’ve periodically dipped my toe into the waters of discussing the “business” of filmmaking; a topic I am, so far at least, fairly lousy at (at least from the perspective of profit). Frankly, as a filmmaker it’s all I can do to break even at the moment, and my go-to joke is that I make money doing and describing post-production so I can lose it doing production.

However, as the odd duck who both works in post and produces original work, I’m in the unusual position of being on both sides of the fence when it comes to film budgets. As a colorist, I want to be paid for my time, and I want a rate that’s commensurate with what I offer as an artist. As a filmmaker, I need to pay a lot of people to get my projects done, so while I want to pay for professionals, I need to stretch my budget and minimize each line item in as non-insulting a way as I can so I can write all checks I need to.

As a colorist, I want to deliver the goods. As a filmmaker, I want to impress the audience. However, as a colorist I’m limited by the number of hours the client can afford; I work hard to maximize that time by being efficient, and I often round down a bit to keep the budget in the box, but I can’t afford to give my time away past a certain point. As a filmmaker, I only ever have so much money that I’m trying to stretch to fit the project of the moment, and that demands various sacrifices that shape the result.

As much as I wish the visual mediums in which we work were entirely divorced from commercial concerns, the truth is that shooting anything more than a webcam video where you’re sitting on your ass is going to involve some manner of financial commitment, whether in terms of dollars spent on rentals and crew, or in time spent on behalf of the volunteers who are sacrificing other things they could be doing in order to fulfill your dreams. Even if you use a phone to shoot an available light comedy sketch with friends of yours that you’re editing into the next hot zero-budget web series, at the very least hard drives cost money. The phone or tablet or laptop you’re cutting on cost you money. The software you’re using (probably) costs money. If you’re going that route, film festival entrance fees cost money. The internet access you use to upload your projects to YouTube costs money. You’re paying, even if you think you aren’t paying.

And I sure hope you at least bought your friends lunch for their efforts.

If you want to do a project of any ambition, that financial commitment grows. By “project of ambition” I mean a project that’s lit by one or more people who know how, that’s shot with a camera recording a high-quality image with high-quality lenses that are being focused by someone who’s paying attention, that has high quality audio recorded on a dedicated device by a dedicated person paying attention to it, that has some manner of camera motion facilitated by whatever type of camera support you can access, that uses practiced actors and interesting locations both of which are deliberately dressed to look the way the story needs them to. In other words, you have more people helping you out, and perhaps more equipment that you either bought, are borrowing, or are renting.

John Eremic, who works at HBO, who’s responsible for Endcrawl, and who knows what he’s talking about, and I had an interesting discussion on Twitter a month or so back about his ongoing assertion that the film industry is ripe for “disruption.” It was spawned by John’s response to the following article (by Canadian Filmmaker Kevan Funk which I wholeheartedly agree with, by the way, itself a response to a prior article to which I had the same response as Kevan).

John’s perspective on our brief twitter exchange can be read here.

I get what he’s saying; by being held hostage to the feature film and television forms of narrative we’re making now, we’re stuck with a system of financing and distribution that doesn’t encourage innovative stories, because the institutions that provide the money for these activities are risk-adverse. The consequence is that either (a) filmmakers dedicate themselves to pitching work that conforms to what studios are willing to buy, or (b) filmmakers do whatever they want, and distributors will cherrypick only those projects they’re willing to buy, based on what the distributors think audiences will attend. In either case, the outcome of what movies are available to people browsing Fandango or Netflix or Hulu or their cable listings for something to watch is the same.

New forms of media that are ostensibly cheaper to produce promise to free media makers from the burden of raising so much money to do their thing, while new distribution methods promise to make it easier to reach an audience and potentially monetize your activity, thereby enabling you to take greater risks on telling stories in novel ways that the more expensive and hidebound forms don’t allow, due to their expense.

Sounds great. I’m all for that.

However, I’ve developed a pavlovian response to the word “disruption,” with its attendant implication that old workers must lose their jobs so that a new guard doing innovative new things can flourish. An implication stated in the title of John’s blog entry, “Do We Want Better Movies, or Do We Want to Keep Our Jobs?”

Clearly, change is upon all of us who work in visual media. The evolution of film and video technologies into digital technologies, whether we’re talking about cameras, postproduction methods, or distribution technologies and strategies, have in many respects reshaped what we do, and reduced the footprint of these activities in terms of both expense and employees.

And new forms have absolutely emerged to compete for the leisure hours of audiences. Video games have become an enormous industry, spawning epic storyline-driven masterpieces that will easily consume fifty to one hundred and fifty hours of your life (I believe I spent 125-odd hours playing through Dragon Age 3, I can’t remember how many hours I put into Skyrim, and I never wanted to know how many hours I put into the final collection of Diablo III). Indie games on both traditional game platforms and on your phone compete for your time against YouTube stars with various followings, and the various streaming services are beginning to experiment with new types of programming with which to retain subscriber dollars with.

These new forms change the landscape in important ways. However, in many ways they don’t. It still takes a lot of people to make a video game or movie or television show of “ambition” (and I use that word loosely). I don’t think anyone in the industry would argue with me when I say that gear is not the most expensive part of any given production. People are.

It’s not to say there aren’t cost advantages that have emerged. Cameras are getting cheaper. Reasonably equipped post suites are nowhere near the financial commitments they once were. 3D modeling and animation software has plummeted in price, and the hardware needed to render intensive scenes has also fallen by amazing amounts. On the other hand, those were always things people could rent or hire for a fraction of the cost of ownership. Don’t get me wrong, easier and cheaper long-term availability of gear and software is an improvement all media producers or laborers, but it’s not the key driver of a modern production budget.

The cost of hiring artists and craftspeople remains the bulk of any budget. Actors, whether on-screen or voiceover. Gaffers and grips. Audio recordists. Stylists. Cinematographers. Makeup artists. Editors. Set decorators. Audio mixers. Wardrobe. Colorists. Stunt people. Coordinators. Assistant Directors. Directors. Screenwriters. Storyboard and Concept artists. Modelers and animators and compositors and previs and model makers and practical effects specialists and myriad other VFX artists. Composers and musicians. The list of available specialists goes on, with each one you add to your budget making a unique artistic contribution that years of experience have honed. One can hire fewer of these specialists and do the remainder of the work oneself, or one can hire more specialists in order to focus oneself more deeply on fewer personal contributions to the work, but the bottom line is that doing any manner of audio-visual presentation, you’ll be needing some combination of other people to create content of sufficient polish to be tolerable to an audience.

Even in other forms of media creation.

The four most solitary media forms I can think of at the moment, web comics, webcam entertainers, indie game programming, and podcasts, are all certainly things that individuals can do. And as such, they’re the most successful forms for truly independent media artist right now, “success” being loosely defined as something an individual can sustainably do in an ongoing fashion without becoming homeless.

This success encompasses everything from (a) being able to do these things as a sideline from day jobs, to (b) being able to quit the day job and be able to make a modest living doing the thing, to (c) upon rare occasions being able to do well financially when the thing somehow grabs an audience of significance.

This is an exciting development, and provides both hope to creators and a fertile body of lively work to audiences. But it is of limited applicability to the narrative short subject, feature-length, or episodic storyteller, or to the game developer doing a larger project involving ever more art, performance, and technology; in these instances, such “works of ambition” of necessity require more than a single person to either break even or be paid. And this isn’t just a matter of “well, shrink the crew,” because from what I’ve seen, even if you only add two more people to your project, you’ve significantly diminished your ability to be sustainable from the modest revenue streams available to the totally independent media creator (direct sales, patreon subscriptions, online ads, t-shirts, swag, etc.). The most successful independent media creators I’m seeing out on the web are one-person-bands. Maybe they hire an assistant to do specific, containable things, but largely they’re working solo to produce work with very low overhead, or that’s subsidized somehow by circumstances unique to that person’s situation (their day job affords certain access to gear or expertise, for example).

If you want to tell a story in a manner beyond a recorded Moth podcast, let’s look at a solid minimum way of going about it, using narrative storytelling as an example. You write the script and direct it yourself. You borrow a DSLR kit from a friend in exchange for lunch. You shoot available light, but get a friend to hold a bounce card for you and generally help with the camera. You write a scenario with the minimum characters necessary to tell the story, three actors who bring their own wardrobe and do their own hair/makeup as necessary. You shoot on private locations arranged by friends in order to avoid municipal permits and the absolute necessity of production insurance (it’s never a good idea to avoid insurance, by the way). However, you realize that without good audio, all your intentions are for nought, so you get another friend with a Zoom recorder, and rent or borrow a microphone and boom pole. After the shoot, you decide to save on post by teaching yourself everything, editing, audio mixing, color grading, title design, you use automated music software to generate a score, and you do all the post yourself. Done.

You’ve still needed the help of five other people. And this scenario depends on you being a good screenwriter, director, cameraperson, person with an eye for lighting, organizer, DIT, editor, sound designer, dialog editor, mixer, colorist, motion graphics designer, and finishing editor. You must do all of those things well in order to have something at a level of quality people won’t turn off after the first 10 or so seconds (or so I’m told).

If we’re talking about stories here, no matter what the medium, there are certain minimums. Someone has to create the story. Someone has to visualize the story. Someone must bring the characters to life. The result must be assembled and fine-tuned. Visuals must be polished. Audio must be polished. The people and the process must be organized somehow. Even for a project in which the characters are drawings on sequential cards brought to life with clever narration, it has to be written, drawn, voice acted, edited, mixed, finished, and organized.

Using any combination of innovative technologies, how many of those things can you do yourself?

How many things should anyone do by themselves?

Additionally, think on this. You’re not just hiring people to do things you aren’t good at doing yourself, or that you can’t do yourself. You’re hiring people to bring an additional perspective to the work being done. You’re hiring people, hopefully, that are in a position of saying, “hey, that thing you thought was a good idea? It’s not, we should do something better, and here’s a suggestion.” You’re hiring people to bounce your ideas off of. The more you undertake to do by yourself, the fewer opportunities you get for someone else to bring value to your creative work, no matter what it is.

And if you’re not paying those people money? Than what you’re doing isn’t sustainable. You’re working at a loss, even if that loss is non-monetary in terms of burning out your volunteer/collaborators over time. I’m not saying working with unpaid collaborators is bad, it’s certainly something that must be done from time to time of necessity whenever you’re new to your craft, but I am saying that it’s not an ideal way to pursue a long-term career.

So that’s why I’m dubious about the disruptive potential of technological advancements and new categories of entertainment for changing how projects are made when multiples of artists are needed. Certainly a bit of “doing more with less” becomes more possible, but while you may have replaced your “cast of thousands” with a Massive simulation, you now need a not insignificant team of programmers and artists to drive the replacement methodology at the same level of quality, that are likely (hopefully?) earning more per-person than those extras would have.

Art, which in my view is hopefully the thing we’re all pursuing here, is a profoundly human engagement with the world. It’s the need of a person to say things to other people. The writing of stories, the framing of images, the realization of characters, the shaping of narrative through the units of shots and scenes, the moulding of audio to draw out the emotional potential of each scenario, the adjustment of color and contrast to perfect each image, the composition of music. Each one of these tasks provides the means for that person to communicate to the rest of us, and requires a universe of skills unto itself. Each part of the process is a craft where having a human practitioner with a point of view is valuable.

I have no doubt that finding ways of automating various of these tasks will increase efficiency and drive costs down, and I have no doubt that machine learning and various other technologies being developed will eventually eliminate the necessity of hiring, say, colorists, as filmmakers will be able to simply point at a style off a menu and have their scene instantly balanced and made to look like that. But where do we stop? Automated story generation? Automated editing technologies? Automated music generation is already upon us, and will undoubtedly improve, but how much fun is it to work with composers and musicians to find the unexpected?

My point of view about where innovation can help, rather than steamroll, the artist is that the overall goal is to empower humans to tell more and different types of stories, and for other humans to exercise their art to help improve these stories. At a certain point, unless the goal is to create streaming services powered by audience-feedback-driven automated story generators and to eliminate humans from the storytelling process altogether, we’re still going to want to find a way for human practitioners to sustainably do audio-visual art.

More to the point, in the face of increasing technology, automation, and innovation, there are still people who are going to want to do things the “old” way. Novels and short stories continue to be written, forms which if you include epic poetry go back for centuries. Paintings and sculptures are still constructed from paint and stone. Comic books are still being written and drawn, increasingly digitally, but still by hand via stylus, colored, and lettered by separate individuals. Over thousands of years of evolving forms, theater is still being made. All of these methods of delivering narrative content to audiences continue to be practiced by artists and engaged with by audiences. Technology has certainly impacted the creation of all these forms, and yet, artistic specialists continue. Authors need editors. Painters hire frame makers. Comics creators employ writers, pencillers, inkers, and letterers. Theater, depending on the production, has its own armies of specialists despite, and perhaps because of, the many more technologies that have become available to the theater production, many of which overlap with cinema and television production.

And so it goes with visual narrative. Technologies don’t alter the fundamental desire for humans to drive the mechanisms used by each of the various disciplines. Steenbecks have given way to NLEs, rolls of film and reels of mag have given way to volumes of bits, and klieg lights have given way to LED lighting, but the decisions about how to use all of these things continue to come from the human artistic impulse.

This isn’t to say I don’t believe in the need for evolution, to improve how media reaches the public and make more widely available the means of visual storytelling to a wider pool of culturally and politically varied individuals, because I agree that there is a problem. That problem is that the business of storytelling interferes with the process of storytelling and the selection of who does the storytelling, even as the business of storytelling enables storytelling at the scale at which mass audiences are interested in seeing it. It’s well and truly a conundrum in need of innovation.

However, visual narrative, be it cinema, series, or video games, or whatever VR content proves to have the most durable audience, require teams of people, and these ought not be considered a liability. Humans are not a bug in the system, they’re a feature, because when you hire right, each one of these people makes the project better. Which is nice, because people need jobs.

Innovation is great, but let’s try and focus it on the things that suck. Let’s not just envision innovation for the sake of eliminating people from a process that, in the long run, probably won’t need us as much as we need it.

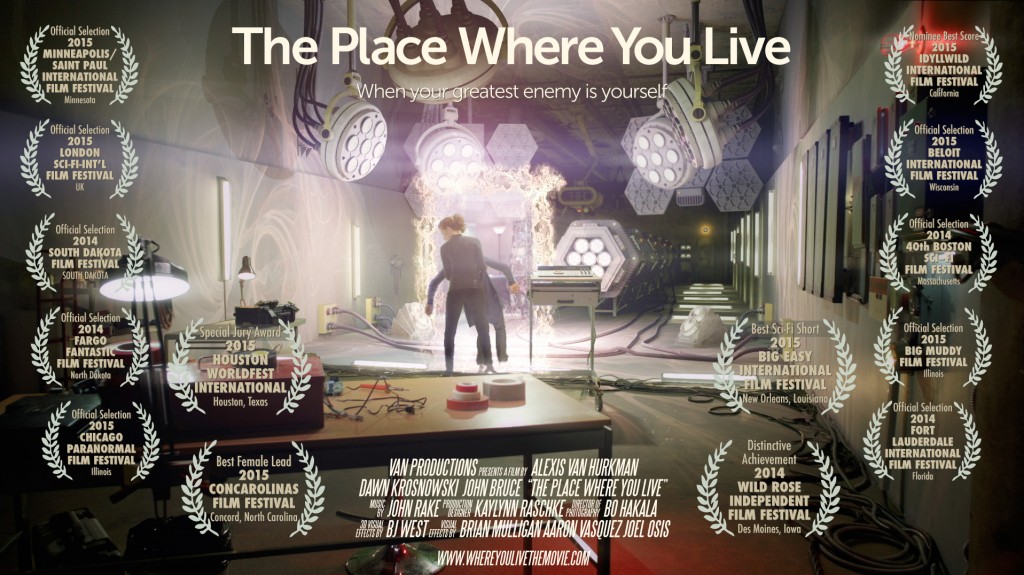

This is it. After two years of production and post-production, and a year traveling on the film festival circuit, I can finally release my Science Fiction short “The Place Where You Live” free on the web to the general public, available both on both YouTube and Vimeo. It’s been a long time coming.

While the shoot itself went fairly quickly, with two-and-a-half days of principal photography, and another day of pickups a year later, post-production took a good long time for everyone involved. It’s tough squeezing in ambitious VFX composites in-between paid gigs, and even I wasn’t immune as this came during the same year I ended up writing and revising a total of five different books (Adobe SpeedGrade Classroom in a Book, Autodesk Smoke Essentials, the DaVinci Resolve 10 manual, Color Correction Handbook 2nd Edition, and Color Correction Look Book), in addition to the color grading gigs I had that year. Squeezing in my portion of the post where I could was hard, and not a day passed where I didn’t wake up and feel guilt over not being able to get to my film (I’m never writing that many books in a year ever, ever again).

In the end, nothing motivates finishing like a deadline, and an early look at the trailer and a teaser convinced the organizer of the Midwest Sci-Fi Film Festival that he wanted my short in their lineup. This prompted my last and most break-neck month of post-production and finishing, to wrap up the project once and for all, and to embark upon what would become a total of 18 festival screenings, plus one promotional screening (in Beijing, no less). In the process, we garnered six awards for everything from “Best Science Fiction Short” (Big Easy International Film Festival) to “Best Leading Actress” (ConCarolinas Short Film Festival), to a “Special Jury Prize” at the Worldfest-Houston International Film Festival. I travelled to what festivals I could, along the way meeting many talented filmmakers, actors, and film enthusiasts at screenings both in the U.S. and abroad.

Film Festivals are always a great experience; films are meant to be seen by an audience, so it’s gratifying to put the work in front of people, which to me is the the whole point. Happily, we had great audiences who were, on the whole, enthusiastic about the film. And being in the Science Fiction category of a lot of festivals, I have to say there’s a lot of really fantastic work out there right now. “The Place Where You Live” was in great company in every shorts program in which it played.

Please watch the credits, as I can’t thank the folks who worked with me on this nearly enough. Additionally, I want to give a huge shout-out of thanks to Autodesk, who sponsored the project, and develop the software that made it possible (the entire short was entirely edited and composited in Autodesk Smoke). Their support was key to this film’s creation, and helped me to get up to speed with an incredibly capable and deep application. Smoke’s fantastic integration of node-based compositing and editing made it easy to tweak every shot in this movie until the day it was finished. Autodesk 3D Studio Max was also used by artist B.J. West to create the CG effects, so Autodesk Software touches every single frame of this film (along with Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and After Effects to create animated graphics elements, DaVinci Resolve Studio to create dailies and do the final grade, GenArts Sapphire plugins to help all along the way, and Avid ProTools to do the sound design and mix). If you’re interested in learning more about the workflow I and the other artists who worked on this project used, you can see a presentation I gave at the 2013 Amsterdam SuperMeet here. In the coming weeks, I’ll be posting a couple more “making of” videos showing preproduction and workflow.

And now, my only appeal. If you like this short movie, please help spread the word among your friends, colleagues, or anyone you know who likes thoughtful Science Fiction. Promotion is one of the great challenges facing independent filmmakers, and word of mouth on social media and in person is one of the best ways you can reward this project if you like what you see.

And so, without further ado, it’s showtime!

Thank you for watching! If you want to read more about our adventures making this film and following the film festival circuit, please check out The Place Where You Live website.

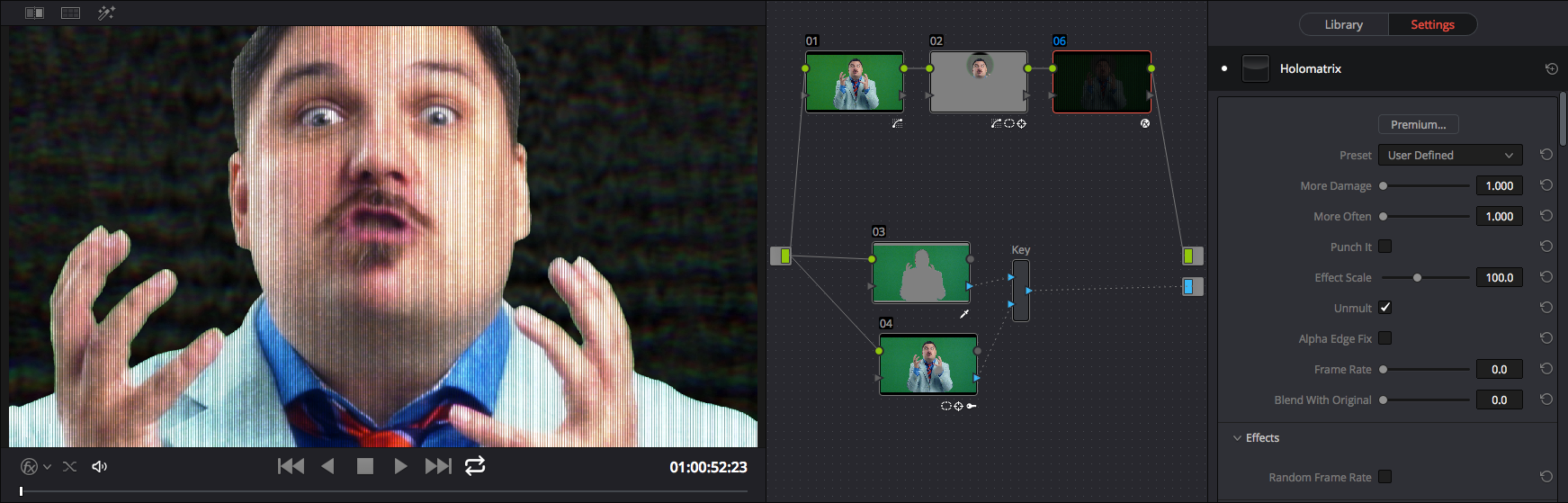

The shoot for my goofy little rant, “The Importance of Color Correction,” came on the heels of some promos that Steve Martin wanted me to record for my newest Ripple Training titles for DaVinci Resolve 12. I figured, since I’m there on a stage, why not have a bit of fun with it?

A confession – I suffer from incurable impatience between a shoot and the beginning of the cut, so once home I immediately fired up Resolve 12 and got to work. I was determined to do the entire thing inside of Resolve, to test the workflow of grading, compositing, cutting, and finishing a green-screen intensive project, all within Resolve 12. Since I knew I wanted to edit a series of dynamically changing backgrounds that reacted to what was being said, my first order of business was to grade the clip, and create transparency from the green background for compositing within the timeline.

I shot with the BMD Production 4K camera, but I made the decision to record to ProRes HQ, instead of raw, as I wasn’t sure how many takes I’d burn through, or how much space I’d ultimately need. This meant that, although I recorded a log-encoded image, my camera settings were burned into the files. The result, owing to a combination of camera color temperature settings and shooting through the glass of the teleprompter I was using, was the following image (after normalizing to Rec. 709 using Resolve Color Management):

After a relatively straightforward grade, this was easily turned into:

This took two nodes. It could’ve been one, but I like keeping my HSL curves separate for organization.

This was the original grade, but since I rendered out self-contained graded clips to hand off to Ripple, I ended up re-importing the graded media and using it as the basis of my next few adjustments and the edit. This wasn’t necessary at all, it just seemed like the thing to do, since I had the media and all.

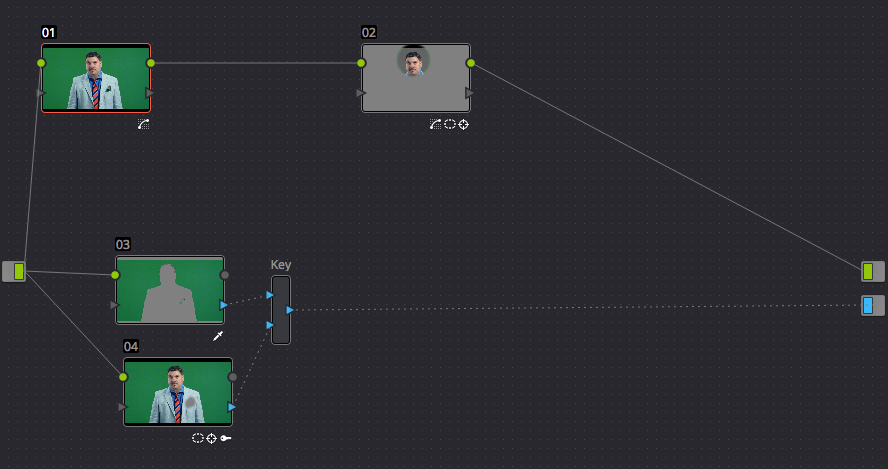

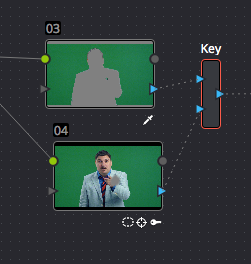

With the grade accomplished, it was time to create transparency, which I did using the blue-labeled Alpha Output in the Color page’s Node Editor, connecting a matte I created using a combination of techniques (nodes 3, 4, and the Key node), while the color adjustment nodes (1 and 2) connected to the RGB output.

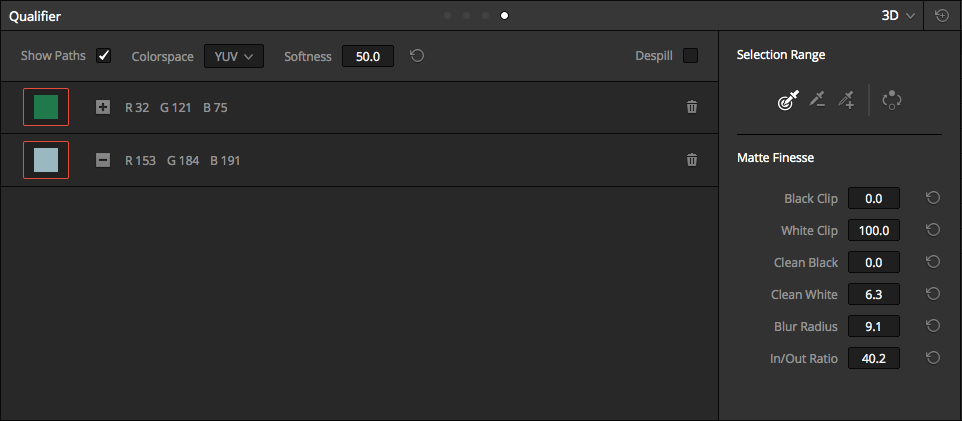

In particular, since some idiot I rolled out of bed and threw on a green jacket with a green pocket square without thinking before rushing over to the stage, I needed to be a bit clever with how I created the matte. Although, being faced with this kind of issue, I was kind of glad to have an interesting test of the new 3D Keyer’s capabilities for green-screen compositing in a slightly awkward situation.

Turns out, the 3D Keyer (in node 3) did a fantastic job of specifically keying the green screen background while omitting the slightly different green of my jacket, while retaining nice edges without too much crunchiness, so big props to the 3D Keyer; it only took one sample of the background green and a second subtractive sample of the foreground jacket to do it (along with very slight application of the Clean Black and Clean White controls).

However, no combination of samples would also omit the green pocket square, which was just too similar to the background. This required me to divide and conquer, using the Key mixer to combine the 3D Keyer matte with a second matte generated by a tracked window to cover the pocket square.

The window itself was easy to make and track, except for the part where some idiot the “talent” decided to wave his arms around.

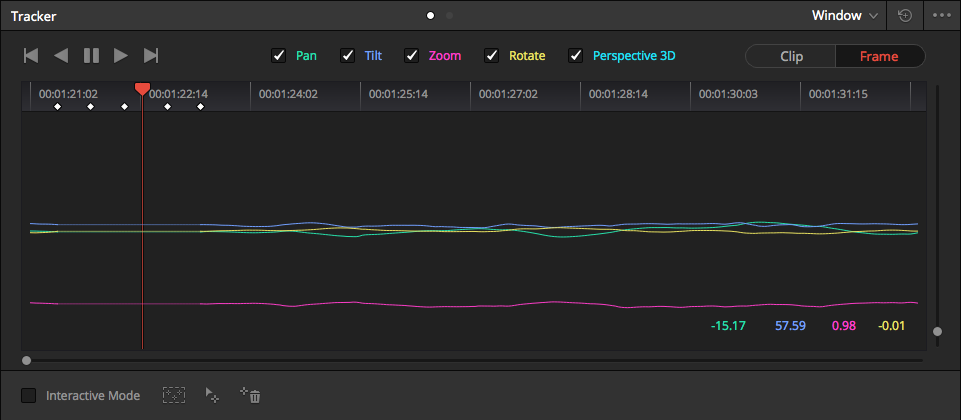

The hand completely screwed up the track, but my body motion was so irregular that just deleting the disrupted part of the track and letting Resolve automatically interpolate between the areas of the clip that had good tracking data wouldn’t cut it (although that was the first step). So, I ended up using yet another one of Resolve 12’s new features to solve the issue, the new Frame mode of the Tracker palette, that makes it easier to auto-keyframe manual alterations to a window’s shape and position (i.e. a bit of rotoscoping). Five manual adjustments (and keyframes) later, and the hole in the tracking data was nicely filled.

Inverting the 3D Keyer matte in Node 3 (using the Invert button within the Keyer Palette) and letting the Key Mixer node add the two mattes together from nodes 3 and 4 gave me the overall matte I needed, which, when connected to the Alpha Output, punched out the background nicely.

Now, however, I needed to deal with the green spill that was figuratively (possibly even literally) hitting me in the head. Sadly, while the Despill checkbox that’s built into the 3D Keyer works wonderfully in situations where the person being keyed isn’t wearing fucking green, in my case I couldn’t use it without leeching all the color out of my jacket. So, time to go back to the old ways, isolating my head using a tracked circular window in node 2, and using the Hue vs. Sat curve to selectively desaturate the greens that I didn’t want contaminating my face.

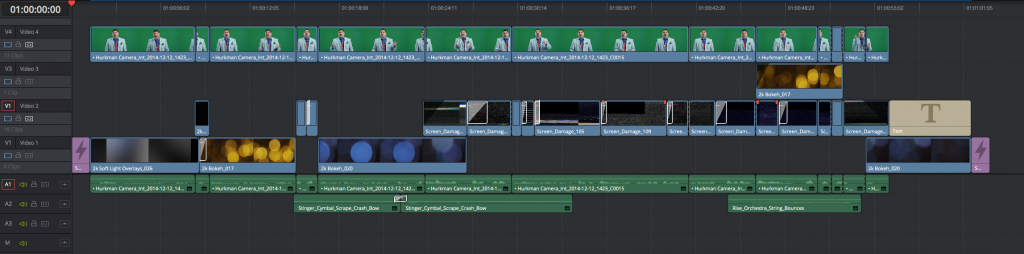

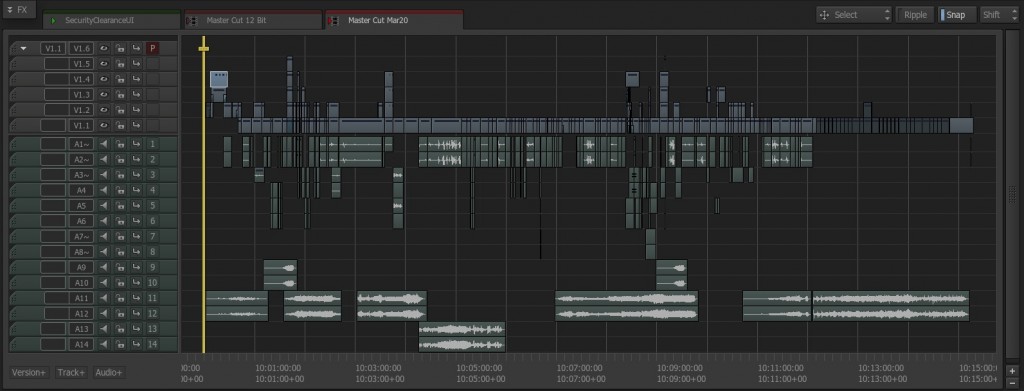

With all that done, I could now go back to the edit page and cut together the varied mix of backgrounds behind the foreground clip. While I was at it, although the entire rant is a single long take (thank you teleprompter), I wanted to chop it up to punch up the rhythm by rippling out a few pauses, masking the jumps with push-ins made using the Zoom controls of the Edit page Inspector. Thus, at the end of the edit, I had a timeline that looked like this:

For the backdrops and audio cues, I used clips from the THAT Studio Effects collection of HD resolution effect clips (licensed from Rampant Design, which offers 2K–5K resolution media). The cut went smoothly, pretty much in real time on my 2010 Mac Pro with Nvidia GTX 770 GPU. (I can’t believe how much life I’ve gotten out of that five-year-old machine.)

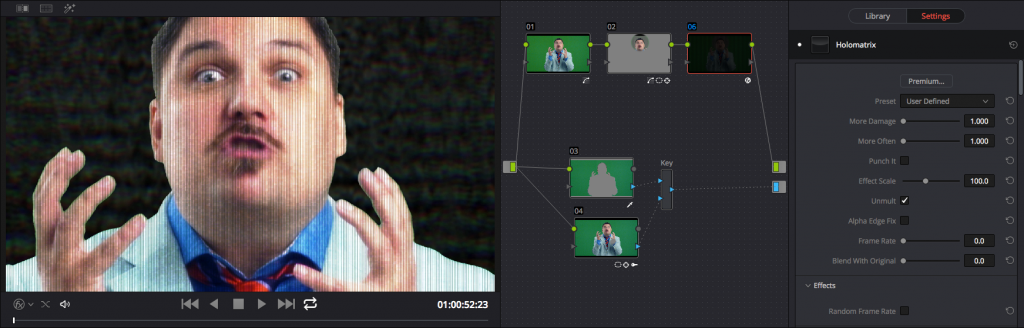

However, I had one last problem. Because I had decided to record to ProRes HQ at 1080 resolution, some of my more aggressive push-ins started to look soft, softer then I liked going out the door. Mulling over how to deal with the issue, I thought it would be funny to try and emulate the effect of zooming into a televised image, such that you’d see the pixels of the TV. Red Giant Universe to the rescue, I used their Holomatrix OpenFX filter to add vertical scan lines (hey, why not) to the zoom-ins, stylizing them to the point where the softness is irrelevant.

And that, as they say, was that. A composite-heavy green-screen promotional piece graded, composited, edited, and finished entirely within DaVinci Resolve. I did the mix as well, but that was nothing to brag about as the first version I uploaded to Vimeo had all of my dialog mixed to the left channel (there’s a reason I send final mixes for my projects to dedicated audio professionals). Still, I fixed the problem, tuned the mix, and completed the program, which you can see in the previous blog post.

All in all, it was a great experience, and while I’m the first to say I’m biased since I work with the DaVinci design team, I’m also being completely honest when I say that I’ve been really enjoying editing in Resolve 12, and using the hell out of all the new grading features, to boot.

(Updated 9/8/15) This is the last update, as we’ve played all of the film festivals that we were accepted to, and we’re not expecting to hear from any more. At final count, “The Place Where You Live” is up to eighteen festival acceptances, and one non-festival screening in Beijing, with six awards presented, and one additional award nomination. They were all great experiences, and the resulting laurels are a welcome addition to our poster.

The final list is as follows:

- BIRTV screening in Beijing (screened August 26th)

- On the Line Film Festival (screened August 7th)

- From the Beyond Film Festival (screened August 8th)

- 15th Annual Sci-Fi-London International Festival of Science Fiction (screened June 1st and June 7th)

- ConCarolinas Short Film Festival (award for best leading actress) (screened May 30th)

- 48th Annual Worldfest-Houston Int’l Film Festival (special jury award) (screened April 19th, 2015)

- 34th Annual Minneapolis/St. Paul Int’l Film Festival (screened April 12th, 2015)

- Big Muddy Film Festival (screened February 26th, 2015)

- 40th Annual Boston Sci-Fi Film Festival (screened February 7th, 2015)

- Beloit Int’l Film Festival (screened February 28th, 2015)

- Idyllwild Int’l Festival of Cinema (nominee for Best Original Score) (screened January 7th, 2015)

- Big Easy Int’l Film Festival (award for Best Science Fiction Short) (screened December 13th, 2015)

- Chicago Paranormal Film Festival (screened November 30th, 2014)

- Fort Lauderdale Int’l Film Festival (screened November 17th, 2014)

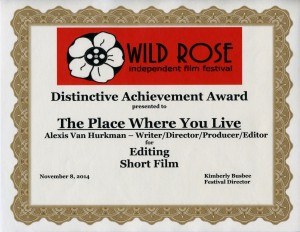

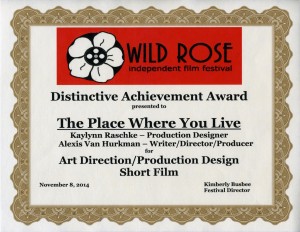

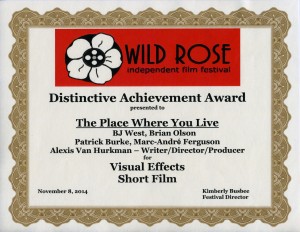

- Wild Rose Independent Film Festival (awards for editing, production design, and VFX) (screened November 7th, 2014)

- Fargo Fantastic Film Festival (screened October 26th, 2014)

- East Lansing Film Festival (screened November 4th, 2014)

- South Dakota Film Festival (screened September 27th, 2014)

- Midwest Sci-Fi Film Festival (screened July 4th, 2014)

The last festival acceptances delayed the public release of “The Place Where You Live,” pushing it to September. Everyone’s been incredibly patient during my film festival adventures, and I apologize for this last push out, but I really hadn’t anticipated the last-minute festival response we got. Still, September is set in stone, and this gives me ample time to prepare its rollout.

As I mentioned previously, my last tour on the festival circuit with my indie feature “Four Weeks, Four Hours” garnered six acceptances, so this is what progress looks like, and I couldn’t be happier.

It’s time for some tough love.

Since I do both production and post, I’m in a position to observe where efficiencies lie all through the filmmaking process. In speaking with different people out in the industry, and comparing my practices with theirs, I’ve decided there’s a public service announcement I can make to the filmmaking community at large regarding how you can save money. A lot of money.

Rehearse your actors in advance of the shoot, dry run your blocking without running the cameras, and record fewer takes.

Really.

I know. You’re thinking “but digital is cheap,” “I don’t want the scene to go stale,” “why not run the camera in case some magic happens,” and “I need to get through those takes to find the scene.”

Bullshit. Digital is not cheap. Hard drives are expensive. Backups are expensive. Archiving camera cards takes time, and having a ton of cards because you want to shoot like a drunken sailor costs in either expendables or rentals. Generating dailies and logging all of your crap takes consumes hours and hours of your editor’s time. Dealing with Terabytes of unused data in the finishing process takes time. Time is money. Time is also frustration, which makes post folks not want to give you a discount. Less media is less hassle, and less hassle makes editors more inclined to maybe cut you a break.

Rehearsing in advance, assuming you have capable actors, will not make your scene go stale; centuries of theater give the lie to this way of thinking. What advance rehearsal will do is let you work through the scene in the abstract, without the necessary distractions of the cinematographer’s queries or your schedule running behind or what scarf should the lead wear or any other of the hundred things you need to weigh in on that have nothing to do with the actor’s actual performance.

In exploring the scene with your actors in rehearsal, I guarantee they’ll find nuances in performance that might otherwise be missed, and you’ll have time to try things out and make adjustments you need for consistency with your overall vision. All of this will let you know where there are moments to emphasize and trouble-spots you’ll need to correct in the performance. Ultimately, you’ll be better prepared for what’s to come. Come shooting day, you and the actors will both know what the goal is, and you’ll be less at risk forgetting about a key moment, gesture, or intention because you were distracted by a lens change. And, in the rush of production, there’ll be more then enough energy to hype up both you and the actors to keep things fresh, since you’re likely in the location for the very first time.

Running the camera while you’re rehearsing your blocking is a colossal waste of storage, unless you’re chasing a sunset or some other time critical element. Whether you’re doing jib, crane, dolly, gimbal stabilizer, or steadycam work, or just panning and tilting a camera on sticks, there is no magic while you and your actors are fumbling your way through the on-set blocking with a camera operator who’s seeing the actor move for the first time. Save your editor the heartbreak of watching four unusable takes and just rehearse the blocking without recording. The actor will be more at ease to experiment, and you’ll have more psychological freedom to change your mind and explore different ways of executing the move with your actor, cinematographer, and operator.

Regarding multiple takes, I am firmly of the belief that if you’ve had the opportunity to discuss and rehearse the scene with your actor in advance (even if it’s in advance of the rest of the crew arriving for a day’s shoot), there should be no reason to ever go through more then 4-5 takes, unless there’s something physically specific you’re needing (I once did eleven takes trying to get a coin to fall on the ground in the right place for a closeup, what are you going to do?). There are plenty of stories of directors pushing an actor through 99 takes to wear them down, which is more strategic cruelty and not so much about trying to get a good read, and that’s fine if you’ve got 100 million dollars. Myself, I’d rather work out what I need in advance through appropriate casting and rehearsal, and then get the scene in three takes and move on to have another setup. Back in my film school days, a production professor told us that shooting twelve takes was probably a waste of time, since you’ll probably be unable to tell the difference between six of the takes later on when you start editing, and I’ve generally found this to be accurate.

So now you’re thinking, “okay, smart-ass, so what’s your shooting ratio?” My most recent project, which was one day’s shoot with over twelve camera setups with some additional alts spread among two locations recording to 4K CinemaDNG raw, ended up totaling about 500 GB of media for 50 clips in all for a generously covered 3 minute scene. Going back to my short, “The Place Where You Live,” four shooting days recording to 4K R3D raw resulted in a total of 487 GB of media. Usually when I mention this, people ask me what went wrong, and what I did about the lost media. Then I say that was all the media.

I started out shooting 16MM film, and being a broke-ass filmmaker I had all too many days of having pages to get through on two 100-ft rolls. Those experiences instilled in me an economy that serves me well even today. And so, I try to be careful about casting. I rehearse in advance whenever possible. I block the scenes with the actors without running the cameras. Then at that point I try to get out of any particular camera setup in 3-5 takes, sometimes altering the framing of any takes I want “for safety” just to squeeze in another push-in. Obviously if an unexpected challenge comes up, I’ll do more takes to get what is needed, but I try really hard to be prepared enough in advance to avoid that.

The result is that I never have to debate whether or not I want to shoot uncompressed RAW based on available storage, my DITs are usually bored, logging the footage is a breeze, and as a result the edit goes quickly. Backing up the project media doesn’t break the bank, and moving the project around for finishing is resultantly easy.

So that’s my advice. Save everyone some hassle and take a page from the theater—rehearse in advance. You’ll get better results dramatically, you’ll get more out of your time during the shoot without going over schedule, and you’ll have a project that should be noticeably cheaper to post.

I’ve been having an enormous amount of fun flying out to some of the film festivals we’ve gotten into, and meeting other truly independent filmmakers who are tilting at the windmills of this crazy industry of ours. While I’m generally just happy to have the opportunity to screen my work in front of actual human beings, I’m thrilled to announce that “The Place Where You Live” won distinctive achievement awards for Editing, Visual Effects, and Production Design at Des Moines Iowa’s Wild Rose International Film Festival.

It was my second festival in two weeks, and while audience response continues to be really positive, this kind of additional recognition is icing on the cake, and a nice bit of validation for all the folks who’ve worked so hard to make this impossibly ambitious project come to life. This is especially true as the Wild Rose International had an impressively strong lineup of films to show, including a pleasingly high number from other Minnesota filmmakers (shout-out to the Twin Cities!).

VFX

Huge congratulations to everyone who pitched in with me on the VFX, most of whom were tragically left off of the certificate (for reasons solely of length). However, I can amend that here by giving a huge shout out to Brian Mulligan, Aaron Vasquez, Joel Osis, Christopher Benitah, B.J. West, Brian Olson, Patrick Burke, and Marc-André Ferguson for his organizational talents putting the original Smoke-based VFX crew together. I couldn’t have done this without this incredibly talented team of artists, and if I were you I’d hire all of them.

Production Design

I’m also excited that Kaylynn Raschke’s contribution as Production Designer has been recognized. An industry veteran stylist with over two decades of experience in commercial styling for print and broadcast, set dressing, and wardrobe, she went above and beyond with limited resources to design and assemble a fantastic pair of environments for the movie, each of which had a lot going on. Production design is all too often neglected in smaller productions, and I’m proud to say that’s not a problem we had.

Editing

Lastly, I’m very pleased to be recognized for the editing of this piece. While I’ve not had my shingle out professionally as an editor for clients since the late nineties, I’ve continued practicing the craft through cutting my own work, that of my wife Kaylynn (a filmmaker in her own right), and in doing the occasional bit of surgery on projects requiring finishing in addition to grading. It’s nice to see that I’ve still got it.

More festival screenings are coming up; go on over to whereyoulivethemovie.com for the latest listings and updates!

It doesn’t have to be perfect, but it does have to be right.

Whether they’re aware of it or not, this attitude is something that I think distinguishes the more seasoned producers, directors, and cinematographers I’ve worked with from those at the beginning of their careers, and it’s something that every artist ought to think about during the course of a project.

You can drive yourself crazy trying to get the artist you’re working with to find the perfect solution to a creative problem. The perfect grade. The perfect cut. The perfect draft. The perfect font. In a quest for perfection, you might try solution after solution, discarding one after the other because of the vague sense that no matter how good what you’ve got is, there must be something better.

This is a fantastic way to spend shedloads of money, consuming inordinate amounts of time creating lots of versions, many of which probably work extremely well to solve whatever creative issues need resolving. But you don’t need five different solutions, you just need one good one. Veteran clients know this.

I contend there’s a better way of framing the quest for creative excellence, which is to focus on finding the right solution to the creative problem at hand. While there can only be one perfect solution (attainable only after a Xeno’s paradox worth of cash-burning variations), there could be many right solutions, and you need only try the first one or two to finish the scene well and move on.

This is not the same as settling for less, or only doing “good enough.” A solution that’s truly right may not be easy, it may yet require a few versions to discover. However, when found, the right solution will achieve the look, timing, theme, or design that forwards your project’s agenda and allows you to move on to the next task in the endless conga-line of things you need to finish. And acknowledging that you’ve found the right solution will spare you the fear, doubt, and uncertainty that “oh god there must be an even better solution out there if only we’re smart and creative and tenacious and RICH enough to find it.”

If you find the right solution, everything should fit together in a satisfying way. Might you come up with an even better solution tomorrow? Sure, but you don’t have to worry about that now, because if something better presents itself, then you can always revisit. And if not, than you probably found the best solution in the first place, and aren’t you glad you stopped worrying about it and moved on?

So that’s my note for the clients and artists of the world. Focus on finding a solution that’s right for your project, and move on.

On the other hand, a piece of corollary advice for the creative professional doing client service is this—a solution that’s right for you might not be right for the client. Many are the colorists/editors/writers/compositors/motion graphics artists/sound designers who’ve pulled their hair out over a client’s rejection of their brilliant solution to a creative problem.

When other folks are paying us to be creative for them, it’s incumbent upon us to reverse-engineer the aesthetic of the client in order to develop solutions that the client will find fulfilling. In an ideal world, those would dovetail with our own inclinations, and those are moments to be treasured. When it doesn’t, it’ll spare you a lot of heartache if you focus on figuring out what it is the client actually wants and why they want it, rather than trying to convince them that your way is better (unless the client is utterly undecided, in which case it’s entirely appropriate to make recommendations to break the log-jam).

Admittedly, this is easier said then done, depending on the personalities in the room.

And this is where I go back to giving one more piece of advice to the clients of the world. If you’ve done your homework, and you’ve hired a skilled artist whose reputation and/or showreel you trust to perform a job for you, keep in mind during moments of uncertainty that you hired them because they write/grade/edit/compose/design for a living, and they’re trying to do what’s best for your project. If you’ve been given a solution that you generally like, but you want to see another version just because you think there’s something better out there but you’re not honestly sure if that’s even true, it’s probably okay to trust the artist you’re working with and move on to the next task.

If you still feel that way tomorrow, you can always revisit, but if you watch that section again and realize that the solution is just right, you’ll feel pretty smart about nailing the project and saving a few hours while doing so.

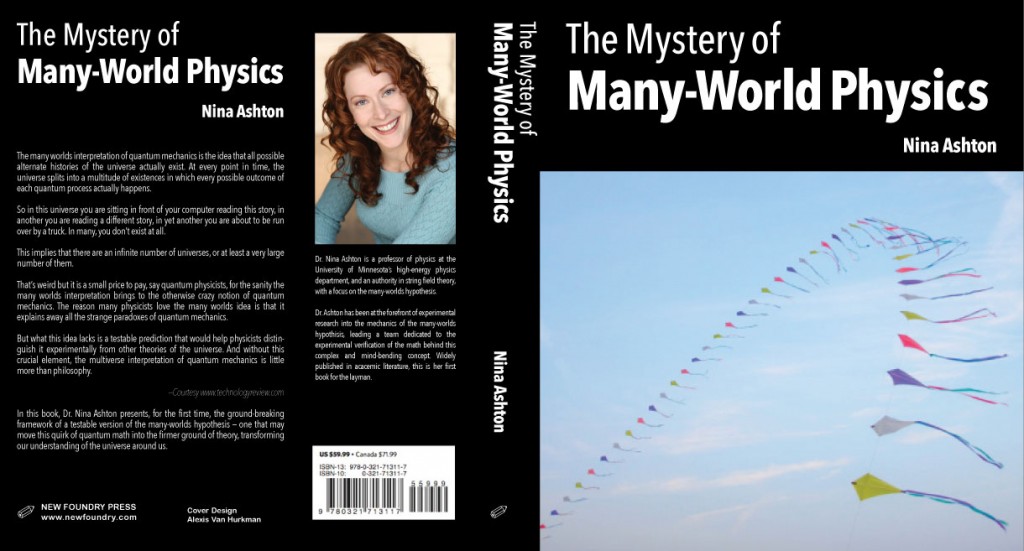

Nina Ashton, a professor of physics, is abducted by her counterpart from an alternate dimension—one in which her husband has died. As her doppleganger takes her place, Nina struggles to rebuild the machine and reopen the gateway between worlds in order to regain the life that should be hers.

I’m very pleased to present a preview of the first two minutes of “The Place Where You Live,” my new science fiction short that’s working its way through postproduction, shot by fantastical shot.

We’re aiming for a May release, and I couldn’t be more thrilled with how it’s turning out thanks to the fantastic cast and crew, as well as the incredible talents of designer and animator Brian Olson, compositors Brian Mulligan, Aaron Vasquez, Joel Osis, and Christopher Benitah, and 3D artist BJ West.

Kelly Pieklo has begun working on the sound design and mix, which can be heard along with John Rake’s wonderful score. I also need to thank Autodesk for their sponsorship of this project (the entire program is being edited and composited on Smoke 2013), as well as Splice in Minneapolis for their hands-on support.

If you want to learn more, I’ve blogged about the production, and I’ve also blogged about post.

And keep your eyes peeled for my next major announcement, once the whole 12 minute film is ready for viewing!

It’s been a while since I’ve posted an update about my upcoming science fiction short, “The Place Where You Live.” In the months since the initial two-and-a-half day shoot, I’ve edited the whole thing together, and after several passes of polish, the final runtime comes to 12 minutes, excluding end credits.

That’s a bit longer then the now quaintly optimistic 8 minutes I was estimating up front, (the shooting draft of the script itself is 9 pages). Having shown it to a few early audience members, it’s a tight 12 minutes that moves along briskly, and I’m pleased. The cut is always the last draft of the screenplay, and being the writer and the editor really hammers that home.

Once I finished the first cut, composer John Rake started putting together the music cues, seven of them in all, so I had something to play off of the visuals as I started my fine cutting. It was a great process bouncing cuts and cues back and forth as we zeroed in on the final timings, and I’m really happy with the score, which has a retro nod to some of the synth-oriented scores I’ve loved from the ’70s and ’80s.

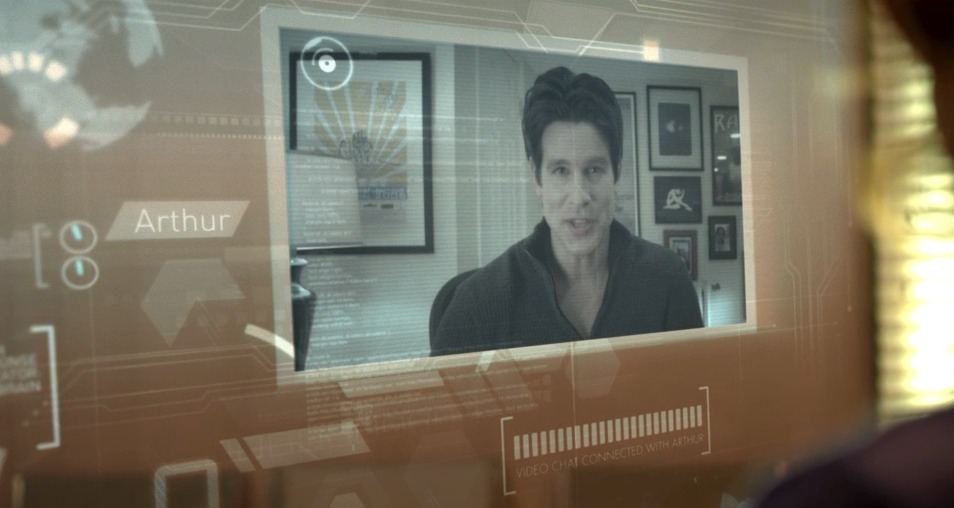

Once I had enough of the edit done to know where I needed to add some narrative space, and how I wanted to handle the scene transitions, I did one last half-day shoot with DP Eli Ljung and AC Erica Wollmering to get some second-unit style driving, hallway walking, and videophone conversation shots accomplished, which allowed me to finish the cut once and for all.

As I cut in Smoke 2013, I took advantage of the integrated compositing to assemble rough comps to identify the timings of each of the VFX plates, and to help test viewers out.

For example, there are a number of shots that visualize heads-up-display technology for all of the computer screens. While I didn’t want to take the time to comp in a whole UI, I did have the reverse half of a videophone conversation that I needed to edit together, which I was able to easily rough in with a picture-in-picture effect using Smoke’s 3D transform environment, using Smoke’s Axis timeline effect to quickly motion track the window to the background for a true “floating window” effect. This is a level of VFX detail I’m not used to having in an NLE, and made it a lot easier for my test audiences to pay attention to the story, and not the effects-in-progress.

Of course, using my primitive compositing as a reference, I was then able, using Dropbox and with compositing supervisor Marc-André Ferguson’s help, to organize and hand off all of the plates to the team of artists and compositors who are remotely creating the final VFX, including the actual HUD graphics (graphics design by Brian Olson at Splice Here, compositing by Aaron Vasquez).

Another compositing artist, seasoned Smoke veteran Brian Mulligan, has been creating the “doorway between dimensions” effect used throughout the piece, as well as rocking some of the more challenging digital duplicate shots of main character Nina and her doppleganger from another reality.

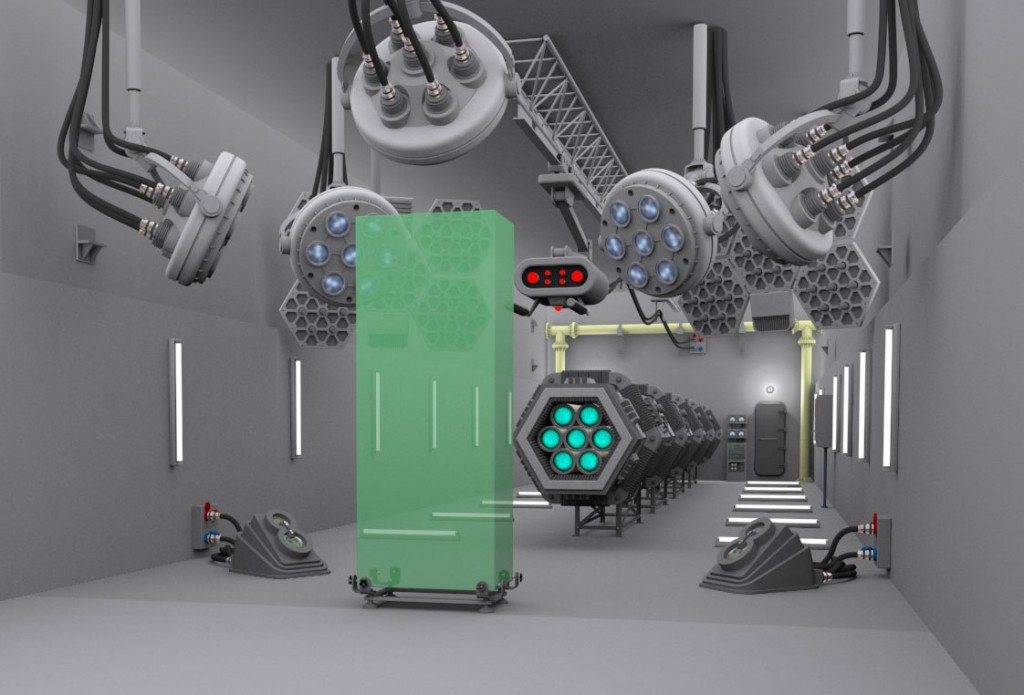

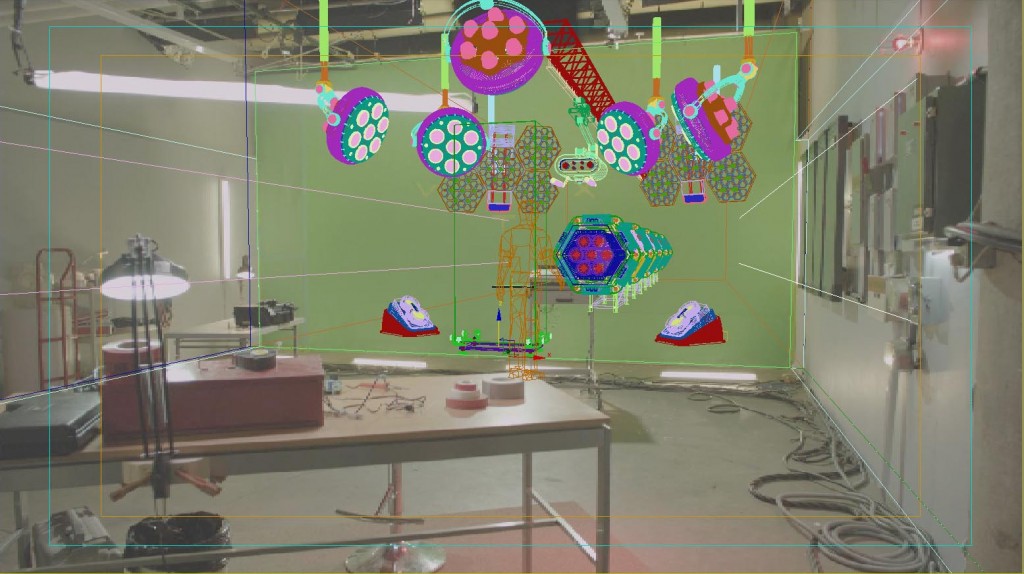

Meanwhile, 3D artist BJ West has been creating the set extension for the lab using 3D Studio Max, building what he’s been referring to as “La Machine.” First, illustrator Ryan Beckwith’s finalized his concept art for the machine.

With that finished, BJ has been elaborating on the initial design, making modifications as I’ve been coming up with changes based on the needs of editorial.

BJ’s challenge has been to fit the geometry of everything so that it matches the space of production designer Kaylynn Raschke’s lab set. My goal is for a seamless digital set extension, and we’ll be sweating the details.

At the moment, all of these VFX shots (57 of ’em) are still in process, but I’m aiming to get one segment in particular finished to the point where I can preview it during interviews at NAB. The rest of it will be completed by the end of April (I’ve just handed off the audio tracks to sound editor Kelly Pieklo at Splice Here, so we’re on our way).

So that’s where the project is now. It’s far and away the most technically challenging piece I’ve ever directed, but all of the elements are coming together beautifully, and I can’t wait to share the final product once it’s done.

Those of you who’ve been following me on Twitter have undoubtedly been noting my now constant stream of preproduction tweets, so I figured it was time to stop being such a tease and share a bit of what’s going on. I’m producing and directing a short subject I’ve written called “The Place Where You Live.” I’m not going to spoil the plot, as you’ll have an opportunity to see it soon enough, but here’s a clue…

The headshot shows our lead, Dawn Krosnowski, who’s heading up a cast of three in this tightly scripted “Twilight Zone-esque” excursion into speculative fiction. Kaylynn Raschke, art director extrordinaire, has been overseeing construction of our two sets for this project.

We’re saving money by shooting in a non-traditional space, in this case, a pair of stages usually reserved for band rehearsals. The tradeoff is that they’re odd spaces, but the advantage is that Kaylynn has had more time to work on the sets, and we haven’t needed such a huge crew.

The last time I had a set built was 1991, since then it’s been all on-location shooting for me. However, it’s nice to be back in a mode where things are more tightly controlled. While not a feature, this is easily the most ambitious project I’ve worked on, with dual set compositing, lots of VFX, and a terrific crew headed up by cinematographer Bo Hakela.

So that’s what all the fuss is about. After six years of being in development with two other projects, it’s nice to be shooting something again. I’ll be posting updates once principal photography is finished, and more as we shift from production into post, and the post specialist in me gets to rue decisions that the director in me just had to make on the set.

I received some fantastic news this week from my collaborator, illustrator Ryan Beckwith, regarding our long-term project, Starship Detritus. He’s been laboring for months on the art for our pilot episode of this animated science-fiction series. This being a side-gig for both of us, his work as a commercial storyboard artist kept interrupting (damn you for being so successful, Ryan!), but getting the news that he’s finished is the biggest leap forward since I finished writing all 13 episodes of the first season.

Of course, now it means I need to get off my backside and start scheduling some After Effects character animators to put these images into motion. Ryan’s been creating high-resolution, multi-layered Photoshop comps (in conjunction with his assistant Ryan Zalis who aided with flatting and other assorted tasks). Working with our first animator, Steve Rein, the artwork has been constructed to accommodate skeletal and puppet-tool animation in After Effects.

Being an illustrator and not an animator, Ryan has gone in a much different direction with the artwork then in most animations. From the very first color tests he did, I was impressed with the texture and detail he brought to the world I’ve written, and it’ll be exciting to see the scenes come alive.

It’s a bit poignant; I used to work with After Effects every day back in the late 90’s, but having been focused on color correction for so long, at this point I’m so rusty that I’d rather work with faster artists to bring these characters to life. I’ll stick to animating the camera and framing of the final comps for rendering out the finished shots.

Of course, as the writer/director/editor, I’ve a few other things to handle. The very first thing I did, after Ryan and I storyboarded the first episode, and he created the first complete set of roughs, was to record a group of temp actors reading the script, and edit together an animatic in order to get the timing of the show right. This has been our reference going forward, and as soon as I get my hands on the full finished set of artwork, I’m looking forward to updating the animatic with the color art.

Which will take a bit of doing. The original animatic was put together in Final Cut Pro, but given this is such an After Effects-heavy project, I’m planning on moving the entire edit over to Premiere Pro in CS6, to take advantage of its AE integration. I’m hoping this creates some efficiencies. Besides, it’s an excuse to learn a new piece of software by doing something real, which I find is always the best way to learn.

Additionally, since this process has ended up taking far, far longer then it was supposed to (par for the course), I’ve begun novelizing this first season. As fun as the 13 episode, ten-minute-per-episode structure I used for the scripts has been, there’s additional story that my chosen format simply won’t accommodate. Prose has been a perfect outlet for the added bits, and the idea of telling this story across different platforms is tremendously appealing to me. At this point I’m 11,000 words into the novelization, and having tremendous fun with it. Alas, now my day job is interrupting, since working on the new version of the DaVinci Resolve 9 manual is proving to make scheduling creative time challenging.

Moving forward, there are plans within plans, and I’ll be sure to share more when there’s more to share. It’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day grading and tech-writing work that I do, but creative projects like this are what brought me into post-production in the first place, and it’s gratifying to be making progress on my biggest creative project to date.

Preparing for my trip to London on the week of June 20th made me reflect on the fact that my very first post on this blog was about another trip to London; a trip during which I pitched a feature/web series project to the director of development of a storied English production company. At the time I was still waiting to hear back, so I didn’t go into specifics.

However, enough time has passed that it seems time to tell the tale. It was a fantastic experience, and in particular involves a funny story about using the wrong tools for the job, and my unveiling of the animatic I created, posted via Vimeo down near the bottom.

Getting this pitch meeting was a four year odyssey of networking, yearly trips to London, and the various slings and arrows of project development. However, once I was over the initial hump of getting my contact at the company to read my script after sitting on it for the previous year, and was reasonably sure that I might actually get a crack at actually getting a meeting, I commissioned a pile of artwork to support my writer/director pitch. The project is a period, gothic adventure–horror tale, with some nice action set pieces. My short filmography doesn’t exactly include an action film, so I wanted to make it clear that I’m fully capable of directing thrilling sword fighting scenes (being a fencer myself, I have a bit of insight).

I hired illustrator and storyboard artist Ryan Beckwith to turn my chicken-scratching thumbnail storyboards into nicely-illustrated presentation boards for the first three scenes. I commissioned concept art from Bay Area painter Anna Noelle Rockwell, who also did a series of costume illustrations for the main characters. I had a practiced pitch. I was loaded for bear.

And then I waited. For various reasons, my interactions with this company were on a yearly cycle, and I had plenty to work on in-between meetings, so I stored my cache of artwork and attended to other business. Once in a while I’d mull over whether or not to convert my presentation storyboards into a whiz-bang animatic, but I decided to skip it, thinking the comic book style presentation of my boards might be more fun to browse. Besides, Ryan and I were already up to our eyeballs planning Starship Detritus (update—the final coloring is nearly done, and we’re going to begin animating shots again for the pilot), so it was easy to relegate to the back burner.

So, as is the way with these things, I got the nod for the actual meeting at the last minute, pretty much a “fly out here in four days and you might get a chance to present” kind of deal. I threw everything together, bought some little easels for the paintings, and re-rehearsed my pitches. Again, I wondered, “should I put together an animatic?” but there was no time.

So, there I am in London, at an afterparty for the event that brought me out there, having gotten an actual appointment for my pitch meeting. I’m at a pub with another producer as well as my initial contacts at the production company, drinking and chatting about pitches, and they start talking about how great it is to pitch with an animatic. And there I sit, feeling like an idiot, since I had a whole year to put something together and I didn’t.

The day before my meeting, I took a walk in Saint James park, mulling. I’d brought JPEG scans of the boards on my MacBook Air, I could maybe whip something together but I didn’t have Final Cut Pro installed because the Air was my writing machine. However, I did have Keynote. Could I do this in Keynote? Absurd! But that night, back at my hotel, I started poking at it, and sure enough Keynote had some rudimentary slide timing tools for autoplaying a presentation. I started putting something together.

Calling my wife, Kaylynn, back in the states, I had her email me a few Yoko Kanno tracks from my iTunes library that I knew, from memory, would fit what I wanted (Yoko Kanno was even part of my pitch, as I would have loved to have her score the project). In a fever, I put the whole thing together and tuned it up by 4am, then caught what little sleep I could manage.

The next morning, while packing up for the meeting, I took one last look at my hacked together Keynote animatic. Was I crazy? Would this fly? I watched it, and, well, it was fun! Not perfect, but it would be a heck of a lot more interesting then flipping through my stack of boards.

With a song in my heart, I went to the meeting. What I though was going to be a 15 minute quick pitch ended up being a fully-engaged hour and a half meeting. I was ON FIRE, and the executive I was meeting with seemed interested. He had his hesitations, but there was a genuine back and forth. And he watched the animatic. All of it (and I did have my finger on the stop key, looking for the slightest sign of boredom which, thankfully, didn’t appear). What follows is an h.264 movie of my Keynote presentation, and while the timing isn’t quite the same, it’s pretty much what I presented in London (vaguely NSFW, I suppose).

After my return, it took four months for them to finally pass on the project, but I’m philosophical about the experience. I’m glad I got the opportunity to make the big pitch I’d prepared for, and for the record, this script isn’t dead. It’s back on my stack again, but I’ve a plan to rework it within a new context when the time seems right. I’ve had too much fun to give up on it now.

My apologies to Yoko Kanno for the unauthorized use of her tracks. However, if you like what you year, and you enjoy soundtrack music, you owe it to yourself to check out her work, which is eclectic and wonderful.

Amazingly, Google has already stuck my blog onto the front page of hits for my name, so I guess I’d better get on the stick with this thing.

Just returned last week from London, where I had the opportunity to put my writer/director hat on to present a project that’s been near and dear to my heart. Anyone who knows me can attest that I love discussing my work, and it was an extremely productive exchange.

Of course, while I was there I had a nice time wandering around the city on Halloween, as well as attending an opening night party for Hammer Film’s London Festival, with a great collection of vintage posters and publicity stills from various movies. Later in the week I also attended a screening of Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter at the Curzon Soho theater, where I got to meet the wonderful Caroline Munro. We chatted about acting and her role in the upcoming film Eldorado (an extremely eclectic cast, and the final performance of David Carradine).

All in all, a fantastic trip. I hope to have reason to return soon.