By now, I imagine most people who know me via social media are abundantly aware that I directed a movie in China, Carry My Heart to the Yellow River, in the summer of 2018 that was finished in March of 2019. It has since played its way through (to date) 24 film festivals in seven countries around the world, winning two awards in the process. Audiences have responded enthusiastically, shedding not a few tears over this heartfelt drama of a high school graduate undertaking an arduous bike trip on behalf of her cancer-embattled friend.

I wanted to share a bit of how this movie was made, because it’s been the closest I’ve come to doing a bit of big feature filmmaking, even within the confines of a 21-minute short. We shot amazing locations in large-format 8K with a great camera and state-of-the-art cinema lenses, the editor and I had months to refine the edit properly, and I got the chance to do postproduction right, grading and mastering carefully considered SDR and HDR versions of the movie, with a wonderful original orchestral score, and a surround mix accomplished in a Dolby Atmos theater.

How Did This Happen?

But before all that, the first question I invariably get at every screening is, how on earth did I, an American living in Saint Paul, Minnesota, get the opportunity to make a sprawling epic short movie in China without speaking Chinese?

The answer is producer Zunzheng Wang, principal at Gaiamount in Shenzhen China, who’s the owner of Zuzheng Digital Video Co, which is the research and manufacturing partner to Flanders Scientific, a company I’m intimately familiar with since (a) I’m friends with American CEO Bram Desmet, (b) I use their displays as a colorist, and (c) they sponsored a previous project I directed. Zunzheng Wang is a formidable hardware and software engineer, an entrepreneur in video technology education, and now head of an emerging media production company, and I’m honored that he approached me to direct his first produced movie.

Since 2013, I’ve been doing presentations on color grading, directing, and screenwriting for Zunzheng at BIRTV in Beijing (China’s version of NAB), even having a screening of my previous short film “The Place Where You Live” as a prelude to a lecture series on directing there. Early in 2018 he approached me about directing a project to be set in Gānnán, in China’s Gansu Province. His interest was in pairing American and Chinese film workers together to learn from one another, while creating an ambitious project with which to introduce his companies’ capabilities. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse, and I immediately got Director of Photography Bo Hakala on board, with whom I’ve collaborated on two prior projects (the science-fiction short The Place Where You Live and the as yet unproduced scripted series Hidden Among Us), which began a two month whirlwind of development and preproduction.

Producer Zunzheng Wang is third from the right, and story author and Screenwriter Kenjing Xiong is second from the right

Writing the Script

Zunzheng introduced me to Kenjing Xiong, who had written an absolutely charming one-page story summary (loosely based on his own experiences). I had already been wanting to do a more emotional drama as my next project, so I was immediately intrigued by this story of two friends, one undertaking an epic journey filled with difficulties in order to send photos to the other, isolated in the hospital fighting an insidious illness. With our combined efforts, him writing three drafts and me doing another two, a shooting script was arrived at with which to begin preproduction.

Kenjing wrote his drafts in Chinese, and these were then translated into English by translator Phillip Yan for my review. I gave notes, which Kenjing implemented in his version, which were then re-translated for me back into English. Once I entered the writing process, I worked from an updated English translation to make my revisions, passing drafts to my inner circle of trusted script readers for feedback as I usually do. Once that was complete, Phillip translated my final draft back into Chinese so it could be used for preproduction in China.

Once I had a chance to do my preparations and make my notes for directing the actors, I sat down again with Phillip and went through the dialog of the script line by line, discussing the intention of each piece of dialog as I would later with the actors. Based on this in-depth discussion, Phillip carefully revised the spoken lines yet again to more accurately reflect the beats of each scene, and the colloquialisms that would be most natural. This was a fantastic process, because it meant that Phillip, who was also my translator throughout the shoot, knew exactly what I wanted in every scene as I gave direction, and I had him on headphones during every take to listen for language details that I wouldn’t be able to discern.

(Front left to right) Translator Phillip Yan, Actress Box He, Director Alexis Van Hurkman, Assistant Director Huan Yang

Producer Zunzheng is a practicing Buddhist who’s been to the region many times and has personal ties there, and he made it clear in discussion that it was vital for us to both show the culture, and portray it accurately. He wanted to make sure we gave the audience many opportunities to discover this region right alongside the main character, a goal I absolutely shared.

I’d spent the immediately previous three years visiting different cities in China while developing a scripted urban fantasy television series with the intention that it be shot in China, so between my expanding Kindle library on Chinese history and culture, and my growing network of friends and acquaintances in Beijing, Nanjing, and Shenzhen, I’d already been cramming both ancient and recent Chinese history and culture, folklore, Taoism, and Buddhism, in preparation for being able to create the Chinese characters of my project. This gave me an adequate foundation to be able to learn more as I worked through what this new project would demand of me.

One of the attractions of this bicycling story is the lead character’s insistence on doing this trip despite her inexperience and the trip’s daunting scale (it’s an overwhelming ride for someone who’s not a committed bicyclist), simply because of her dedication to doing this for her friend. It struck me as a sentiment rooted in the quintessentially Confucian definition of righteousness, “doing for nothing,” or doing something simply because you know it to be right, particularly when you know you may not succeed. Coupled with the Confucian concept of “knowing Ming” (translatable to accepting fate, destiny, or simply the way things are going), this story struck me as a great way to explore a character trying her best knowing full well she might fail to reach the destination in time, as her friend’s condition is completely out of her control. Nor is this simply some narrative conceit; “I’ll try my best” is a phrase and attitude I hear in China a lot, in movies and from friends and colleagues. And so, these concepts drove my evolution of the story in the final draft, and were very much ideas I tried to incorporate into Box’s portrayal of the character.

Narratively, it was the lead character’s status as a tourist herself that gave me the means with which to engage with the culture of Gānnán, despite having been given only two months to give myself a crash course on all things Gānnán-esque. The actress I cast in the lead, Box He, was an 18-year-old native of Shenzhen, which is one of China’s largest and newest cities, and at the time she was between high school and college, just like the character in the story. The Gānnán region was as remote to both the character and the actress as it was to me, so we were both able to share the newness and wonder the character felt traveling through the region, and incorporate it into the project. In a way, it was almost like shooting a documentary, albeit with an emotional narrative driving the journey.

Bicycling scene from Carry My Heart to the Yellow River

The Crew and the Gear

I have to give Line Producer Jianlan Li massive credit for pulling together a crew in record time for the two separate regions we’d be shooting. We had four shooting days on stage and on location in Shenzhen with a larger crew to cover actress Linaixuan Wang’s hospital scenes the backstory of the relationship between the two girls. Then we’d have one travel day to fly up and drive over to Gānnán, with an additional twelve days on location in Gansu and Szechuan provinces with a smaller crew to shoot the bicycle trip itself. This may seem like a princely amount of time for a short subject, but as you’ll soon see there were a lot of company moves; we were covering many different geographical locations over a wide area, in extremely remote locales. Time went fast.

(Left) Line Producer Jianlan Li

Producer Zunzheng wanted to have this project shot in 8K, and chose the RED Monstro camera system for us by virtue of buying a pair for his company. DP Bo Hakala, who’s had a lot of experience shooting RED, was more than fine with this camera system’s vista vision-esque sensor size, resolution (8192×4320), and improved low-light performance. After some discussion, I was persuaded by Bo’s suggestion we shoot full sensor and crop towards the top of the frame for the 2.39 aspect ratio I wanted to use, rather then shooting anamorphic. We were going to be shooting in a variety of conditions, and this approach was deemed both more flexible, and more conducive to being able to shoot handheld given the size of the lenses under consideration, not to mention being a better match for the drone footage we knew we were going to be shooting. I ended up being very happy with this decision later in post.

RED Monstro in standard configuration

When it comes to lenses, my philosophy as a Director is to let the DP choose once I’ve communicated the vibe I want from the image. At Bo’s recommendation, we used a set of Cooke S7 primes, both for the “Cooke look” and for their full sensor coverage. The resulting combination was absolutely magic, allowing Bo to create some truly stunning photography on this project. I believe we also had one exceptionally wide Sigma lens, which we used for certain interiors where we really wanted to give a sense of the space.

Cooke S7 prime lenses

I love working with Bo, he’s a creative DP and impeccable photographer who’s also a wonderfully accommodating collaborator. He’s always able to bring the coverage I request to its best visual potential, and he’s always quick to suggest a better angle or approach when he sees it (usually he’s right), but he’s also able to let go when I need something different. And he’s been able to deal with the fact that I’m a colorist in addition to director, with opinions that occasionally infringe on his world (he did say once that it was bizarre working for a colorist/director). In particular, this project was always intended to be mastered in HDR, so we had a lot of discussion as the shoot went on about what that would mean, which definitely affected the coverage I went for in many situations since we were shooting available light for most of the on-location exteriors. However, it was in these situations where Bo’s photographic ability shined, as he always had a great sense of how to use the best light in every situation. In the end, all of these combined efforts made this project a pleasure to grade, and the fact that he and I had discussed the intention for the images in such detail made it easy for me to put all that thought into the final finish at the end.

Director Alexis Van Hurkman and DP Bo Hakala taking a moment to discuss coverage

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention First AC Eoin McGuigan‘s masterful camera builds and focus pulling. For various reasons we only ended up having one camera body available to us for the shoot, and since we were constantly bouncing among standard configuration, hand-held, Easy-rig, and a stripped down Ronin configuration used both for hand-held and a variety of vehicle mounts, Eoin had his hands full building and re-building the camera multiple times over the course of each packed day of shooting. We tried to be strategic about covering each scene to avoid unnecessary torture for him, but it was still an enormous amount of work.

(Left) Translator Phillip Yan, (Right) 1st AC Eoin McGuigan

While on location in Gānnán, Bo had a veritable one-man lighting and grip crew in Beijing film industry veteran Li Xin. Whether it was setting up lighting on an adjacent rooftop, building a variety of automotive rigs, or attaching lighting or camera to god-knows-what, Li Xin figured it out and executed everything swiftly and safely.

(Left) DP Bo Hakala, (Right) Gaffer Li Xin

The other image maker was Yiyuan (Evan) Feng, the drone pilot who flew the DJI Inspire 2 with Zenmuse X5S camera we used for the shoot. Shooting raw CinemaDNG with a 5K sensor and interchangeable Micro 4/3 sensor and lenses, the resulting footage intercut and graded to match the Monstro footage amazingly well. Evan was a terrific pilot with great instincts, and when he wasn’t working solo shooting B-roll or using the drone to get us ahead with our scouting, he worked well flying the drone in tandem with Bo operating the camera to get us some really great aerial photography.

(Center front) Evan Feng piloting the DJI Inspire 2 drone

My Production Designer for this project was Kaylynn Raschke, with whom I’ve worked on every narrative movie I’ve made in the last twenty years. I never tire of saying that her work is one of the primary reasons my films look so good. Kaylynn was, as always, in charge of all wardrobe, makeup, set design, and set dressing decisions, working with Bo and I to harmonize what needs to go in front of the camera. Working with her team, she then put together looks for every scene with a flawless sense of style, coupled with a keen sense of narrative. A talented writer and photographer in her own right, Kaylynn carefully selects each garment and object on screen, to help tell the story in ways both subtle and clear.

An example she likes to use to illustrate this point is the paint-covered blue shirt worn by the character of Yu Xuan (the sick friend) in the art room scene. It’s actually a duplicate of the shirt worn by the mother later in the hospital, a fact nobody will consciously notice, but that builds a subliminal association between the two characters (one might assume the daughter is using one of the mother’s old shirts as a painting smock).

The movie is filled with examples of this kind of thinking, each decision carefully made to reinforce who the characters are, what’s happening in the story, or giving us clues about what’s important in the frame. Since Kaylynn and I are married, we always have ample time to discuss the project at hand, both in advance and during the shoot, so communication is never a problem. And on set, she’s a tireless organizer who’s not afraid to get hands-on with any issue that comes up. I’m lucky to have her.

(Right) Kaylynn Raschke, Production Designer

On this movie, Kaylynn’s department included Bozhao Dou as Set Dresser and Lillian Fu as Makeup Artist and Costume Supervisor. They all had their hands full coordinating props and wardrobe to match the relentless continuity shifts from one set of shots to the next. There are many time shifts from scene to scene, and a lot of montages, so making sure the character was wearing the correct clothes for the right moment of the film was a challenge, especially with the locations changing as much as they did.

Shooting in Shenzhen

Since Gaiamount is located in Shenzhen, we did that part of the shoot first, with Linaixuan Wang playing Yu Xuan (the sick friend), and Box He playing Jing Yi (the bicyclist). All hospital scenes were shot over two days on a standing set two hours outside of Shenzhen, which Production Designer Kaylynn Raschke dressed to be a modern Chinese hospital. An unexpected power outage in the suburb we were shooting the afternoon of the first day led to delays, but we were able to get back on track that afternoon, and make up for lost time on the second day.

Behind the scenes on the Hospital set (Photo: Eoin McGuigan)

The third day we were able to shoot classroom scenes on location at a Shenzhen college, with a class of film students on hand to be extras. The location was fantastic, and the hallway and classroom scenes went smoothly. As an aside, I learned that all students in Shenzhen city schools wear the same unisex school uniform that consists of mix and match track suits, shorts, and polo shirts, so that made wardrobe easy…

Classroom scene, all city school students wear uniforms

Production Designer Kaylynn Raschke had a bit of excitement when it came to the art room scene, however. Kaylynn and Bo had scouted that location without me (I was hung up in Singapore on business when that particular scout happened, so I approved it based on photos), and the art room they found was perfect as it was with layers and layers of art, models, sculptures, and stuff, so that Kaylynn simply requested the room be left alone. Unbeknownst to anyone on the crew, however, a broken water pipe days earlier flooded the room and it had to be completely emptied out, to the bare walls.

DP Bo Hakala and Production Designer Kaylynn Raschke finessing the art room set

Kaylynn only found this out a half-hour before we starting moving out of the classroom, but she’s a pro and in a whirlwind of activity she and her crew dressed that location back into an even greater multi-layered glory, which with Bo’s finishing suggestions and lighting ended up being one of the most beautiful interiors in the movie. This scene is also one of my favorites in the HDR-graded version, given the rich colors and interesting range of tonality at play. I wanted the scene to be a still life of a still life, and it was perfect.

Art room scene from Carry My Heart to the Yellow River

This location also ended up providing one of the biggest cultural lessons I received during the shoot. I tried really hard to avoid directing the characters to behave with “Americanisms,” and I felt fairly confident that my experience in China thus far, coupled with the fact that I cast actors who were exactly the right age and experience for their characters and whom I could rely on to “be themselves,” would help me avoid any obvious issues. Furthermore, I relied greatly on my growing rapport with Box to communicate with me whenever she felt what I wanted was at odds with the naturalism of the situation. I primarily saw my job as protecting the actors enough from the external stresses of the shoot to feel emotionally comfortable working through each scene without artifice, and as time went on I ended up putting more and more of what I saw in Box into the character she portrayed.

However, during the rehearsal for the art room scene, a woman on set who’s my age came to me and quietly suggested that perhaps the girls were being a bit too emotional, suggesting that Chinese women were typically more reserved than I was portraying. It’s my policy to always make myself open to suggestions from any crew member, so I thanked her for her input, and gave it a moment’s thought. I was basing my direction on people I knew and current events literature I’d been reading, could I have gotten the characters so wrong? We still had a few of the film student extras available for background, so I walked over to one of the young women who was watching the proceedings and casually asked what she thought of how the scene was playing, whether she could relate to how the characters were behaving. She replied, “she’s fine, she seems like any of my friends at school.”

Trip planning scene from Carry My Heart to the Yellow River

It occurred to me at that moment that, given the explosive changes in China that have been happening in the last 20 years, the generation gap between the life experiences of people in their twenties and those in their forties is unimaginably huge. People in their forties remembered the very the tail end of the cultural revolution, and grew up in a more isolated China evolving from the economic policies of decades prior. Meanwhile, urban people in their twenties have grown up knowing nothing but a strong, more western-facing China, with endlessly growing cities and nonstop economic growth. Of course there would be a difference of opinion on character attitudes, but I knew I was on the right track following my actors instincts, reflective of a younger generation’s more casual openness. This could be seen in abundance once the camera stopped and the young people on the crew went back to being themselves in-between setups, so I breathed a sigh of relief and carried on.

The fourth day we shot in a rented bedroom, for the after-school scenes between the two friends. We rented an Airbnb room for the day to do the shoot, which I hesitantly agreed to. We got the perfect location, but I was constantly worried that we would be shut down, either by neighbors or the building owner whom it was impossible to contact in advance. Happily, my concerns were unfounded as we were able to keep enough out of the way for nobody to care, and we ended up simply being another curiosity over the course of the other residents day.

Shooting in cramped quarters in a rented one-bedroom apartment

Shooting in Gānnán

When it came to shooting in Gansu and Szechuan provinces, our schedule was bound by a logistical window within which we could shoot in the second half of July. There was no way to schedule Bo and I doing a preliminary scout, so a scouting team went up to Gansu first, searching for the locations we needed and taking photos and VR videos as they went (the VR was legitimately helpful). Based on this information, a route was planned, but this was only a basic framework for what scenes would be shot where.

The reality was that each area was so rich in location possibilities, in many instances it wasn’t until I could see each place for myself that I was able to make sensible scene assignments. Coupled with being at the whims of weather, trying to find places that weren’t only appropriate for the story but safe for the talent to bicycle on, and having a lot of territory to travel which impacted the number of shooting hours we had in any single day, I ended up doing a lot of schedule rearrangements as we went.

Furthermore, we had local representatives from various tourism boards with us as advisors showing us additional locations that were nearly always extraordinary, giving me an overabundance of choice. All of this reinforced the pseudo-documentary approach I took to this project, with nightly script polishes and rewrites to account for all the new geographical and cultural information I was receiving. Funnily enough, the process wasn’t that different to how I approached my feature “Four Weeks, Four Hours” fourteen years earlier, which also had frequent location changes that influenced that script’s evolution as we shot.

Flying into Lanzhou, which was the nearest major airport, we drove across Gansu Province to the city of Hezuo, the capital of the Gānnán Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, which is an ethnically Tibetan region of Gansu province. It’s an area that’s remote even for most Chinese, and while not in Tibet itself, the gradients of overlapping populations in that area of the world mean that Tibetan culture is everywhere you look, from the language, to the attire of people in the street, to the monasteries, to the Yak herders throughout the grasslands and mountains, through whose herds our production vehicles had to thread as we made our way from location to location.

I’m not kidding, traffic driving through yet another herd of Yak

To American eyes, there’s a distinctly cowboy vibe to the region, with horse and cattle culture everywhere you look. Cowboy hats and bluejeans are mixed with Tibetan long-sleeved garments, local dresses with aprons, and other traditional styles; leather boots and sneakers could be seen in equal measure. You can see people herding cattle from horseback all over the region, although there are also many who use motorcycles (often with a riding blanket over the seat). Yak herds are seen grazing everywhere, while the mountains also have terraced farming communities.

A mother and son we met at the flower park location

Yak milk, meat, and jerky are ubiquitous to the visitor, and coffee in hotels is virtually non-existent in favor of “Yak butter tea” which I learned online is black tea made with a large amount of Yak butter, toasted barley powder, and milk curds. It’s good and I availed myself of it, but if you’re a coffee-in-the-morning person like me, it’s not nearly enough caffeine. I was extremely grateful for Kaylynn’s decision to bring a big bag of instant coffee packets (Starbucks) to keep me on the level every morning.

I found Bruce

Yurts can be seen outside of town, often in use as weekend cabin getaways. Prayer flags stream here and there across the countryside, and buddhist monasteries large and small are evenly distributed from community to community. In town, red-clad monks are ubiquitous. Wherever you go, there’s no mistaking that you’re not in the eastern part of China any more, even linguistically. There were several small communities we shot in where some residents only spoke Tibetan, and our local drivers needed to interpret for our Shenzhen-based translation team. In town, signs were mostly bi-lingual, with both Chinese and Tibetan characters.

China’s a big, ethnically diverse place, and while I had grown reasonably familiar with the culture in eastern China’s larger cities of Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, Gānnán was an entirely different setting. I have to give enormous thanks to our advisors on the project, notably Xaobing (Shirley) Han (who also plays the woman at the Monestary), a practicing Buddhist who answered each of my thousand and one questions about the regional practices and locations, to make sure we were using each place appropriately and that we were behaving appropriately in more sensitive locations. She was an infinite wellspring of knowledge about the culture and customs we were putting before the lens as we shot locations that had never appeared in a narrative movie before. She was only supposed to be with use for a few days, but she generously extended her time to include nearly the entire shoot, and her help was invaluable.

Xiaobing Han at the Labrang Monestary

One of my many goals for the story was to show the everyday modern life of the region and people as honestly as possible. Happily, the vast majority of local residents we engaged with, many of whom we ended up using as actors or extras, were interested in the project and couldn’t have been more helpful, which was great as we ended up shooting in some extremely remote communities. Most places, there was time to have a chat with local folks, which I always treasured. And there were constant requests for photos. Production Designer Kaylynn Raschke ended up being an ambassador for we four Americans on the crew much of the time, since once she was done coordinating wardrobe, props, and whatever location-dressing was necessary, she had time to meet bystanders while Bo, Eoin, and I were immersed in getting each scene in the can.

In fact, we often ended up being a tourist attraction for the locals. Apparently we were the most Hollywood thing to ever appear in those parts. We were given great welcomes from most of the cities and towns we visited, which was wonderful if a bit confusing to an indie crew like us, but the real fun was when we shot in really small villages and towns.

Being given a welcome at the Gānnán border

In Ga’ermacun, a tiny, nondescript town in Szechuan province, my translator took me aside to communicate something an old woman was telling her friend amongst a group of locals who had assembled to watch us shoot some b-roll, which I’ll paraphrase as “are those people ever silly, shooting a movie someplace like this…” We also met lots of folks with recommendations of additional places we could shoot, which was always useful, sometimes heartbreaking as our schedule didn’t allow for too many detours to investigate new opportunities.

Chatting with Ga’ermacun entrepreneur Phuntsok (2nd from right), giving us tips for shooting in the region

Given this was a drama with not a lot of dialog, it was fairly easy to rearrange scenes as necessary to take the best advantage of the locations we were getting into. A typical day would have us getting to the next location, and Bo, Kaylynn, and I would immediately scout around as I figured out what I wanted to do with it. Bo would then make his suggestions for lighting and coverage, we’d go back and forth discussing a bit, then I’d do a quick walkthrough with the actors, and based on all that, a plan would be set. As equipment was shifted, Box would run her lines with AD Huan Yang, whose background as an actor and stuntman (and director in his own right) were invaluable in working with Box, who had stage experience as a dancer and performer, but for whom this was her first film. Huan went beyond typical AD tasks, reading off camera lines for actors to play off of, and helping Box learn how to fall correctly during our one stunt scene, in addition to organizing our background talent and assisting in shepherding the crew as usual.

Assistant Director Huang Yang (center, in cowboy hat) as the crew learns to make the “heart” finger gesture for photos

And what locations we had. I can say without hyperbole that we were privileged to shoot some of the most beautiful places on earth. Our project had the support of local tourism boards, which gave us access to so many extraordinary areas. We had to keep reminding ourselves that we were shooting a short, not a feature, and I didn’t need that much coverage of every single place we were, tempting as it was. A result of all this, however, was that this short movie has more locations than any sane filmmaker would ordinarily try to shoot (we travelled something like 804 kilometers/500 miles of locations in 12 days), which adds immeasurably to the epic sweep of the protagonist’s journey.

So Many Locations

We began our shoot in the capitol city of Hezuo, having obtained permission to shoot at both the main city bus station and a bicycle shop. In both places we were able to get actual people to play their onscreen counterparts. At the bus station, we had a ticket-agent play herself. At the bicycle shop, we asked a local businessman we met if he’d be interested in playing the bike shop owner. English speakers won’t be able to hear, but the result was local characters speaking with local accents. Fortunately, I’ve a long history of working with non-actors on my own low-budget projects, so I was prepared for working this way (it requires lots of patience and a slow evolution of each performance). While there was much discussion about casting in advance, and we tried finding local professional actors, there’s really no film industry in that region. The only way we were going to have authentically local detail in the performances was to find and work with local people. It was a bit harrowing at times, not being sure we’d find the right characters in time for each place, but in the end I’m very happy with the results.

We were fortunate in getting permission to shoot at Labrang Monastery in Xiahe, considered one of the most important monasteries in Gānnán, and a place where to my knowledge no one had yet shot a narrative movie. It was a stunning location, and we worked hard to follow the rules and not ruffle feathers. By and large, we succeeded, but it was a challenging place in which to maneuver, and one of our trickiest days of shooting. The next morning we were allowed to fly our drones around the monastery in the morning light, and those shots make for one of my favorite musical montages during the film.

Drone shooting at Labrang Monastery

After that, we found one of the best roads for shooting bicycle footage near Amuquhuzhen. A newer, wider road with wide shoulders and little traffic. Even better, it was right next to an incredibly picturesque flower park, with a monument to the horse-riding peoples who inhabit this land. The whole area is astonishingly beautiful.

One of my favorite locations was the town of Langmusizhen, where we shot the hostel scene. This town has a real backpacker vibe, and is one of the last stops before going to the truly remote areas in the mountains we were to shoot next. Mountain streams were channeled along streets with local hotels, gear and art shops, restaurants, and cafes, and the entire town was ringed with the mountains we’d eventually be traveling through. There was also a notable monastery with surrounding landscapes that had been flagged by scouting, but unfortunately we didn’t have the time to include that region in the shoot.

Scouting Langmusizhen

Upon arriving the night previously, the red-lit signage was so striking we just had to shoot the “late-night arrival” scene there, and the hostel where we shot the next morning was the very image of what you’d expect from a place catering to adventure travelers. A bit of early morning lighting and one of the smoke cookies Bo brought to add atmosphere created another beautiful scene.

Shooting the hostel interiors

Funnily enough, we ended up having some bonus time when a rain storm up in the mountains washed away the road we needed to use to travel to the next location, and we needed the wait out that afternoon for the road to be temporarily rebuilt so we could get through. That leg of the trip was pretty exciting as we went off-road in our coach bus, but that’s life shooting on location. You never know what’s going to happen.

Four-wheeling a coach bus over a temporary dirt road that was built an hour before

From there we made our way to the newly built town of Tewo, where we spent the night drinking beer and eating hot pot to celebrate traversing the valley. While there, we spent the next two days shooting the bicycle accident, driving scene, and the call to home scene at the nearby mountain village of Luohong. The mountains all around us couldn’t have been more gorgeous, and the residents were incredibly helpful and accommodating.

Shooting at Luohong

I’ll always remember beginning to shoot a dialog scene on a narrow mountain road when the sound of Tibetan-language techno music started wafting through the trees; the villagers had an outdoor pavilion where they would eat lunch, and they were playing music on a loudspeaker while cooking. I honestly hated to ask them to turn it down. It’s a memory I referenced for the music that plays in the movie’s restaurant scene.

From there we had an epic drive to Ga’ermacun. In theory we were only there to stay the night on the way to the Yellow River, but that town was such a great example of the kinds of communities you’d see cycling around that region, and it ALSO had some of the best Yak jerky I’d yet had (in an effort to catch up on my sleep, I had more than one late breakfast after the crew finished eating consisting of spicy yak jerky, mango juice, and instant coffee gulped down en route to the next location). I liked the jerky so much I got permission from the woman running the shop to shoot there.

The Yak jerky shop in Ga’ermacun

While leaving town, I spotted a bridge that was perfect for a cycling shot and stopped the crew to shoot it. Because there aren’t actually that many roads in the region where we felt comfortable putting the actress alongside traffic, I was starting to worry that we weren’t shooting enough bicycle footage for a movie that’s about bicycling, so I started pulling us over wherever I saw an interesting shot worth taking. While we were setting up, a group of teenage monks came up to us, and happily agreed when we asked if they’d like to be in the movie (you can never have enough background).

Shooting on the bridge

Afterwards, we made our way to the ninth bend of the Yellow River, which was perhaps the peak location of the entire shoot. We had one day scheduled there, and I knew the weather would decide whether that would be the epic finale to the movie, or an overcast disappointment. Happily, the weather cooperated. The original story that was pitched to me wasn’t specific about the ultimate destination of the main character, just that it was a place that was important to her sick friend. When I posed the question to Producer Zunzheng about what locale would have that kind of significance within the region we’d be shooting, his response was the Yellow River. Further research confirmed that to me as the obvious choice, given it’s widely considered to be the birthplace of Chinese civilization, and is in fact one of China’s premiere tourist destinations (not to mention one of China’s greatest photo ops).

The Yellow River, as seen in the movie

Getting this shot was no easy matter, as the best overlook that Bo and I could find required an hour-long portage of the gear up the same wooden stairs you can see in the movie. Racing the sun, we managed to get everything carried up and situated in time to get every bit of coverage I needed to carefully control the edited drama at the end of the movie, including some spectacular drone footage.

Racing the sunset to shoot the climactic scene

As we’d been shooting for over a week already, the crew had really come together, and being able to make such a challenging day such a great success was a peak moment. There’s nothing like nailing the hero sunset shot after beating the clock to pump a crew up.

The following day we had the pleasure of being able to shoot monastery interiors at Yijilongwa. At most monasteries, we were prohibited from shooting interiors (we could shoot anything outside the walls, but nothing inside). However, here we were given access to every room, which was astonishing. Funnily enough, another crew had lighting gear positioned for shooting they would be doing after us, so we had to avoid getting their instruments in the background. This was probably the most “doc-style” scene we shot, using the extra wide Sigma lens we had and shooting a handheld walkthrough of the actress through the space, and it made for a real moment of wonder in the movie.

The Monastery at Yijilongwa

Another truly affecting location we were given permission to shoot was the prayer-flag filled monument at Waqie’ercun. Towering structures hold numerous cylindrical pagodas, each of which contains the remains of a local monk (believed to protect the area with their presence). These were surrounded by grounds with streams and streams of prayer flags hanging from posts, making pavilions.

Still of Pagoda scene

The logic behind the prayer flag is that each flag contains a page of scripture. Since reading scripture is a way to gain merit in one’s life, the non-literate may gain access to this merit-building by hanging these flags so that each time the wind blows a flag, merit is earned. This is also the rationale behind the prayer wheels that are also seen in the movie. Each cylinder of the wheel contains a page of scripture, so that turning the wheel earns the same merit as reading that scripture. The context of the scene we were shooting, between the character and her mortally sick friend’s mother, made perfect sense in this location that, to area residents, connotes both mindfulness and hope.

Prayer flags at Waqie’ercun

At this point in production, all I really had to fret about was the beginning, which required a picturesque mountain road on which the character’s bus would be seen entering the region. We ended up staying in the town of Aba (where we shot the restaurant scene), and outside of town was a road to a mountain park, which served up multiple types of gorgeous scenery, from the rolling green foothills that we used for the show open, to the streams and rivers seen outside the bus window.

The opening scene from Carry My Heart to the Yellow River

A few more kilometers down the way, the landscape morphed into the craggy mountains seen later in the movie as we follow the lead’s struggle to reach the Yellow River in time. My only real regret from the shoot is that we didn’t have any more time to spend hiking these incredible locations, as we were too busy filmmaking.

Mountain Park near Aba

There were many more locations, too many to mention in the limited space of this article, but suffice it to say that Gānnán encompasses some of the most beautiful scenery to be found anywhere. This last video shows a broad cross-section of locations that really communicates how much work this project was, and how much fun we had.

Postproduction

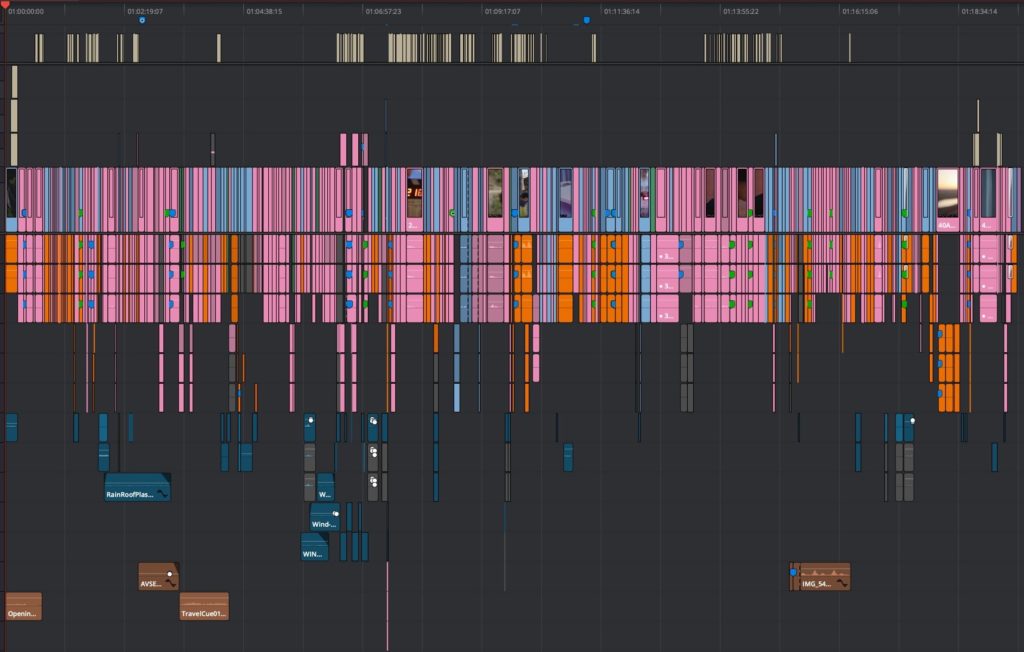

With the conclusion of the shoot, it was time for post-production to commence. Immediately upon returning to Shenzhen I worked with Kenjing Xiong, this time as an editor, to cut a teaser for the movie. He did the first cut using Final Cut Pro X on an iMac using a set of best-of dailies I’d handed off, but when I took on the next edit to add my changes, I decided for expediency to reconform back to the camera original R3D media in DaVinci Resolve. I was using an HP workstation with an Nvidia RTX6000 card, so I could edit at quarter resolution in real time, and once done I could immediately commence the grade. I started with an HDR grade, as I knew that Producer Zunzheng wanted to show this at BIRTV, and I did a manual SDR downconversion from that for web playback. This workflow went so smoothly that I replicated it later during the final finish.

With the teaser, Zunzheng could immediately see what we had. The footage was beautiful, the narrative was working, and it was clear that we had the raw material to create an affecting short movie. With that in mind, it was easy to push forward. I took it upon myself to be the post supervisor since Davinci Resolve would continue to be the center of my preferred workflow, and worked up a postproduction budget to proceed in the most efficient way I could, planning for a healthy editing schedule, original music composition with orchestral performance, and a surround sound mix. I’d be doing the grading, partially to save money, and partially because there’s no way I was going to let another colorist have all the fun doing an HDR grade of this material!

Editing

At the recommendation of colleague Katie Hinsen, I hired New Zealand editor Chia Chi Hsu to edit the program. Her day job is as an assistant editor, but she’d done enough editing that I felt comfortable working with her, and I liked the delicate sense of editing I saw in her reel. Logistically, she also met this project’s needs in terms of being bilingual, being willing to edit in Davinci Resolve (version 15 at the time), and being fine working with me as a collaborating editor, should I feel I wanted to step in. I understand editors who aren’t interested in this, but I’ve been a hands-on editor my entire career, and while I very much enjoy someone else taking the reins, there are times when it’s just easier for me to make some trims right in the timeline as a pass, as opposed to writing up a page full of notes. Chia was great to work with, and we had a productive collaboration on this project. I wish I had a picture of her to share, but at the time we never met, only speaking over WhatsApp and exchanging project files online.

I used DaVinci Resolve to sync the audio (the dual source audio had timecode sync) and create a set of ProRes Proxy dailies from the 8K R3D source that Chia could edit on her laptop. All dailies were output as 2K clips that matched the source media’s aspect ratio, so that any stabilization or reframing during the edit would scale correctly to the source media’s native resolution. I also output log-encoded dailies with RED’s WideGamutRGB and Log3G10 color science as the output settings of Resolve Color Management (RCM). This ensured that any color adjustments made to the dailies by the editor would also be correctly applied to my preferred color settings for the raw source media during finishing. Granted, the low bit-rate, 8-bit, 4:2:0 media wouldn’t hold up for extreme adjustments, but enabling the Rec 709 settings in RCM instantly produced nice-looking SDR dailies, which could be pushed and pulled just enough to even out small exposure shifts that could distract from the editing. I dislike having editors cutting log footage, as I strongly believe that seeing even an approximation of the intended color will affect shot choices. All of this ended up being a great way to work towards the final finish, even while in offline.

All of these settings also went into the project I created for Chia to use as a starting point, which included having RCM set up correctly, along with having an output sizing preset applied to automatically provide the correct framing that was protected for during the shoot; cropping the full sensor to 2.39 vertically off-center towards the top. This was at Bo’s suggestion, so in the event we ever needed to produce full-frame 1.85 or 1.78 aspect image deliverables, the composition headroom would still be reasonable, with the additional pixels coming from the bottom. For good measure, I inserted the source file name and source timecode as window burns along the very bottom of the frame, to aid troubleshooting reconforms later on, while remaining largely out of frame.

Processing log-encoded dailies in Resolve, the red border is an approximation of the framing used for protecting the image during the shoot and cropping in postproduction

I organized the project and media I was giving Chia to facilitate easy relinking and reconform between the source media and the dailies. I also input metadata, finessing the Scene and Take metadata, and adding character, framing, and location metadata (in the form of keywords), as well as customizing the clip names with metadata-driven variable-based clip names, to make the clips more immediately useful. I then shipped a hard drive with the dailies and project file off to NZ, and kept a clone of that drive and its data for myself, for troubleshooting. This was Chia’s first project using DaVinci Resolve for craft editing, but she was a quick study, and I was on hand to answer any questions and deal with any issues since I know Resolve pretty well.

After an initial conversation about the project, Chia did an unsupervised cut remotely. I’m very happy to let an editor have their time with the material without me pestering them. At this point I don’t honestly remember how long she took for her first cut, but she hit the deadline we agreed on. Once I had a chance to see it, we had another conversation about what I liked and what I didn’t, and she went back and did the next cut. The main thing I failed to communicate earlier was my intention to use jump cuts and rapid-fire editing; the source footage was so languid, beautiful, and deliberate one would be forgiven for thinking that was the intended aesthetic for the movie, but the result was not what I’d planned. I did a quick re-edit of the open to provide a more concrete example, and that put us both on the same wavelength better than any amount of notes I could have given. With a clearer view of my plans, Chia’s second cut was right where I’d hoped it would be, and she did another couple of passes before it was time for her to leave the project for a previously scheduled commitment.

At my insistence, the initial edit was done without music. For a narrative project like this, I’ve come to believe over the years that if a scene doesn’t work without music, then it doesn’t work. Music should make an already strong scene stronger, not be a crutch for adding emotion that a scene doesn’t already elicit. As a writer/director, I feel that if a scene needs a musical cue to work, then I’ve not done my job well. Furthermore, I’ve suffered the slings and arrows of “temp love” in past projects, so I didn’t want to get attached to anything but the story. In retrospect, I feel this approach worked really well for this project.

At that point, taking on the continued evolution of the edit was a luxury. All the hard work was done, and my main task was primarily incremental, to take the 26 minute cut she gave me, compress it down, and add a bit more density to some of the montages. This project was always destined for the film festival circuit, and I wanted to see how short I could get the runtime to improve our chances of acceptance. The low water mark I’d whittled the movie down to was 19 minutes (including credits), and my reviewers and I agreed that at that point the story lost much of its charm, and started becoming a mechanical exercise in storytelling. So, I added breathing room back and the final result came to be 21 minutes. I knew going to the festival circuit with a cut this long was going to make my life tougher (spoiler–it probably did), but this was the cut that told the story I wanted to tell in the way I wanted to tell it, and it worked well with my test viewers, so I decided to take a chance and go with it.

Once Chia came back from her vacation, I sent her my edit to review to get her opinion, along with any specific notes that she had. She gave me some great feedback, and with a couple more passes back and forth to address additional improvements, it was complete. Overall, the one scene I found myself re-cutting the most at this point was the ending. Overall, it was good, but it took watching a few variations with different test viewers to really lock down the version that was most effective. I feel fortunate to have the circle of friends that I have, as this feedback was invaluable.

The Feb 11th version of the timeline, close to locked, seen in Davinci Resolve

Music and Audio Post

The score was by Michigan composer John Rake (soundcloud here), with the exception of the cue that plays while the main character is being driven up the mountain that plays in the pickup truck, “Up the Hill,” which was by written and performed by Lillian Ying. John and I have worked together on four projects, now, and his focus on orchestral work has dovetailed nicely with my goals for a sweeping musical experience on this piece. I wanted to bring him to Gānnán to experience the region and meet some of the musicians I’d met while there for inspiration, but unfortunately the winter was too severe for this to be logistically feasible, so I gave John some topics and musical genres to research in order to get ready.

After seeing a music-free rough cut and discussing the project, he suggested a chamber orchestra for an intimate, yet emotional sound. It didn’t hurt that the budget for a Chamber Orchestra was favorable, so once the edit was far enough along for me to have a sense of how I wanted the music to function, he began writing musical sketches and outputting electronic versions that I could review to give initial impressions. He did his music notation using Steinberg Dorico, and for my review he output MP3 files using the Native Instruments Symphony Series libraries for the Kontakt player. Once I was happy with the approach for any given cue, he would flesh it out and send me updated versions with timing to drop into my edit.

In this way, it was easy for me lay his music into the edit, iterate through editorial and music changes, give notes, and get updated cues to continue the cycle. The last of this was done while I was traveling through Southeast Asia, editing and reviewing from my laptop in hotels in Bangkok and Singapore, as the final recording was to be late-January, to deliver music in time for the audio post sessions which were booked for February. John accommodated countless tweaks and timing changes as the edit slowly assumed its locked state, and the resulting cues fit the movie like a glove.

The final music was performed by the Detroit Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Jherrard Hardeman. They did a beautiful job, and the resulting recordings were edited by John and delivered to Department of Post with plenty of time to spare. After listening to electronic approximations for the last two months, hearing the results of actual musicians performing the work was a revelation; night-and-day better than the previews. I had a tear in my eye when I heard the mixed version in the theater for the first time.

(At left) Composer John Rake watches, Conductor Jherrard Hardeman and the Detroit Chamber Orchestra on stage

After exporting the project via ProTools AAF from Resolve to ProTools (and a bit of troubleshooting owing to issues in Resolve 15 that have since been fixed), sound design and mixing was done by the folks at Department of Post, in New Zealand. Because of my scheduled travels, I was able to attend in person to participate in spotting and mixing sessions, which was a treat in their brand new surround sound mixing theaters. Re-recording mixer Alex Chalcoff, sound effects editor Luana Barnes, and the entire team at Department of Post, including workflow supervisor Katie Hinsen who suggested I give them a try in the first place, did a fantastic job. And it was delightful having an excuse to spend time in New Zealand.

Re-recording Mixer Alex Chalcoff at Department of Post in New Zealand

Finishing

Returning to the United States, it was time for the home stretch of the final finish. This included finalizing the movie’s VFX, subtitles, end credits, and grade.

VFX

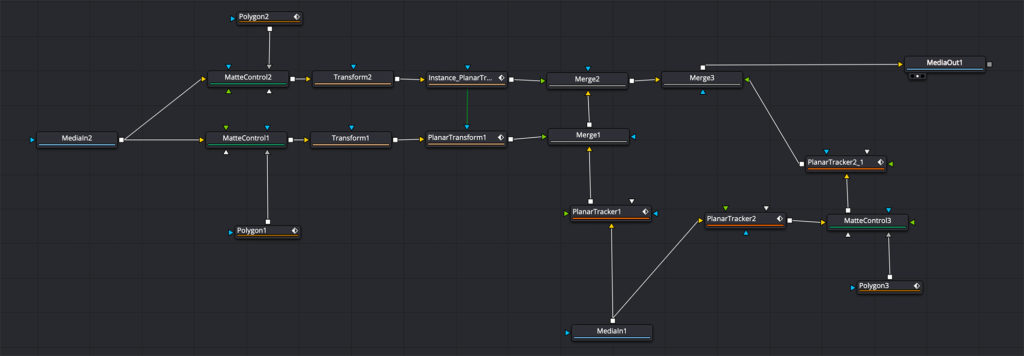

Owing to the nature of the project, there wasn’t a lot of VFX. What there fit into two categories, phone screen replacements, and split-screen effects to accommodate a bicycle crash scene, and occasionally to combine two takes into one when the situation merited it. I went ahead and did the relatively simple split-screen effects myself, using the Fusion page of DaVinci Resolve. I was only planning on doing mockups of the necessary shots in Resolve for someone else to finalize later, but the result was so good that I ended up just finessing the Fusion effects and using them in the final.

A Fusion node graph, within DaVinci Resolve, for a composite I created to combine two takes into one, adding some unplanned background activity to a take with a better foreground performance

The phone screen replacements were more complex, however, and I wanted them to be totally seamless. The hectic schedule of the shoot made doing practical phone screens not feasible, so I used an in-house team of artists at Gaiamount in Shenzhen to design the Chinese-language phone app graphics for the texts that the girls would be sending to one another. These multi-layered graphics files were sent to Splice, a Minneapolis-based post house that has done VFX work for many CW, AMC, Netflix, and Hulu shows you probably know (Arrow, Legends of Tomorrow, Walking Dead, Daredevil, and Runaways, to name a few). I used to do a bit of freelance grading there years ago, and I knew their work was great as they’ve done VFX for some of my other projects. And of course they’re local to me, although ironically I never ended up going into their office, as everything ended up being exchanged online.

At my request, all effects were done at 8K resolution to match the source, preserving my freedom to either push into shots or master at 8K (which at one point was discussed, but so far hasn’t been done). By and large most of the VFX weren’t complicated (though there were a couple of shots that were pretty involved), and there were a few shots that needed to be redone to accommodate a last-minute editorial change for clarity. I hate breaking edit lock, as it’s something I try to take seriously to save money (and sanity), but I got some important last-minute feedback from a filmmaker I know in Beijing, which dovetailed with a couple nagging doubts I had. It ended up being a good decision.

Grading

I actually did the HDR grade of the movie in late December of 2018. This was before editing was locked, but I had a window of time during which I could borrow an XM310K from Flanders Scientific over the holidays. Now, the whole reason I wanted to edit in Davinci Resolve was so that last-minute editing changes would easily be accommodated by color grading without the need to re-conform, so I was comfortable grading the project earlier. Hooking up the display in my home grading suite, I created a 4K HDR master and a quickie SDR downconversion that was fine for post (knowing I’d revisit it later). My window of time was limited as I had travel planned for January-March of 2019, but over four careful passes I got the HDR grade of the 21 minute program master done. The XM310K is an absolutely gorgeous 4K display, and grading HDR on it is a pleasure. At 31 inches, it’s also a perfect match for my smaller home color suite.

Grading the HDR master

Dolby was generous enough to loan me a Dolby Vision license to enable the software CMU built-into DaVinci Resolve, so I was able to set up my Linux-based SuperMicro system to output to SDR and HDR displays simultaneously in order to follow the Dolby Vision analysis and trimming workflow. It was great getting my hands on the technology for a narrative program like this while having the right displays for the job, and I did another three passes with this workflow to see what I could do with it. Months later, after returning home from New Zealand, I did a manually trimmed SDR grade using my own methods, for comparison. I find it funny that my SDR downconversion grade is considerably more complicated than my initial HDR grade.

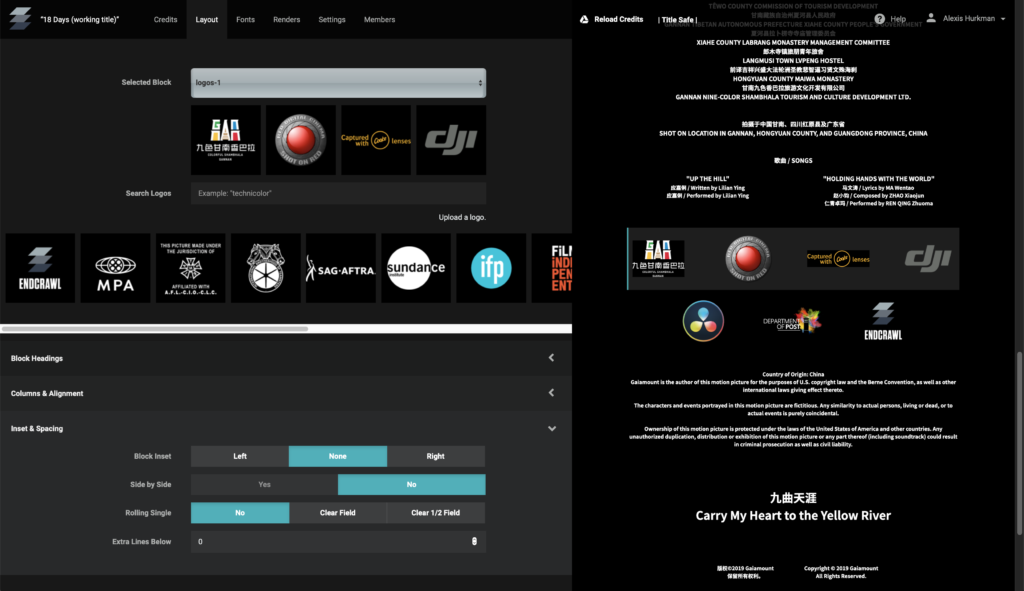

End Credits

The end credits were another task that I was able to begin early, actually starting the process while I was traveling, using Endcrawl. I have to give Endcrawl huge props for making my least favorite thing to do in all of post, credits, actually enjoyable. Starting with a spreadsheet given me by Line Producer Jianlan Li, I was able to share the resulting Endcrawl-linked Google Sheet with my colleagues in Shenzhen, working with them on the translation (I wanted to do bilingual credits), verifying each name and spelling on the list, and tracking down the last few names we needed. Keeping this document dynamic made it easy to regularly update the credits layout at a moment’s notice, no excuses.

The web-based interface made styling the credits a pleasure, and they were very accommodating of making sure that I had a Chinese-compatible font and that I was able to get end-of-credit logos they didn’t have in their database uploaded for my use. Finally, the online rendering system made kicking out new versions with different timings a snap, and paying for 4K rendering made it easy for me to render out separate, properly scaled and timed versions of the credits for each HD, 2K, and 4K deliverable I created. I also appreciate the ability to output the credit scroll at a variety of prescribed speeds; while the recommended speed look gorgeous, I knew this movie would be playing within blocks of other shorts, and I didn’t want to be the jerk with glacially slow credits holding up the next movie. When I master the final release version (for wherever the final release ends up being) I can switch back to the recommended speed, and I had the credits music cue timed appropriately for the added duration.

Overall, it’s a great system that I can’t recommend highly enough, with nice typography and a lot of industry-specific thought put into the details of the layout options. And in the year I’ve been using Endcrawl, they’ve been adding improvements in a steady stream.

Laying out end credits using Endcrawl

Deliverables

In the end, I created a family of deliverables with which to take on the festival circuit, with SDR and HDR versions, at UHD letterboxed, 4K DCI scope, 2K DCI scope, and 1080p letterboxed resolutions, mixed and matched with 5.1 surround and stereo audio mixes. So far, festivals have played only the SDR 2K scope and SDR HD letterboxed versions, in both surround and stereo sound. I have, in my collection, an HDR 4K Scope version that nobody outside of Shenzhen has seen, that I desperately hope can someday find its way to audiences. It’s drop-dead gorgeous. However, that will have to wait until our festival year is concluded and I see if I can interest an HDR-delivering streaming distributor in our character’s epic journey.

Conclusion

When I started writing this article, I had no idea it would break ten thousand words (I guess there’s a reason I’ve put off writing this for six months), but it’s been a huge project with a lot of moving parts for a short movie. It’s been massively rewarding, though, and I’ve enjoyed every part of the process. I couldn’t be more proud of the final result, and of the huge amount of effort that everyone involved has put into it. A director is nothing without collaborators, and I’ve had some great ones. And I have to give one last thank you to Zunzheng Wang at Gaiamount, for having the vision to put this project into motion, and for pulling together the resources to carry it through.

I’ve since directed another project in Shenzhen, giving me the opportunity to learn more about one of China’s most dynamic cities, but that’s a topic for another time. I hope someday to be able to return to Gānnán, simply to travel and take things in outside of the bustle of a shooting day. There’s so much more to experience, we only scratched the surface.

I hope you someday get to see the full movie; I’ll certainly be announcing it here once it’s move widely available.

2 comments

[…] extremely proud that “Carry My Heart to the Yellow River,” the short I directed and co-wrote in China in the summer of 2018, has found such a global audience on the 2019-2020 film festival circuit. So far, this uplifting […]

[…] the Frame.io team, I mentioned how fantastically useful the platform was for my last film in China, Carry My Heart to the Yellow River. I told them I used Frame.io extensively throughout my whole workflow, but they were particularly […]